Marc Bohan, the creative force behind Christian Dior’s most iconic collections for three decades, died on Sept. 6 at age 97 in Châtillon-sur-Seine, France.

According to a public notice on the site Libra Memoria, religious services are scheduled for Sept. 13 at the Saint-Nicolas church, to be followed by a cremation.

Bohan was the longest-serving designer at Dior, longer than even founder Christian Dior himself.

An intensely private man, known for an even-keeled nature and for a proclivity for designing clothes for “real women,” he often boasted of an affinity for a “timeless notion of beauty.

“I make clothes for real women, not myself, not for mannequins and not for fashion magazines,” he said in an interview with WWD on the occasion of his 25th anniversary at Dior. “I gladly leave the abstract creations to others.”

Looks from Christian Dior spring 1985 haute couture collection designed by Marc Bohan.

Guy Marineau/WWD

His reputation was for conservative good taste, but flecked with humor and clever references.

“My style remained constant over my career,” Bohan said in a 2007 interview with WWD. “I wasn’t designing for anybody except for the women who were my clients. It was important that they feel beautiful.”

Bohan was born in Paris as Marc Roger Maurice Louis Bohan on Aug. 22, 1926. His father, Alfred, was a banker, and his mother, Genevieve, was a milliner who encouraged him to go into fashion.

Bohan developed a reputation for creating stylish, feminine clothes for a wealthy, privileged clientele that included Princess Grace of Monaco; her daughter Princess Caroline; Queen Silvia of Sweden; Sophia Loren; Elizabeth Taylor; Babe Paley; Claude Pompidou; Danielle Mitterrand; Barbra Streisand; Ann Getty; Niki de Saint Phalle; Betsy Bloomingdale; Bianca Jagger; Anne Bass; Estée Lauder; Maria Callas; Nan Kempner; Carroll Petrie; Sylvie Vartan; Irith Landeau; Brigitte Bardot; Nastassja Kinski, and Arielle Dombasle.

Marlene Dietrich, the designer told WWD in 2007, was “a bit stingy” and added, “She preferred to have her suits made in the men’s department. It was cheaper. But it also suited her.”

Bohan’s signatures included short jacketed suits and pants worn with very long vests, along with blouses and dresses with Pierrot frills at the necks and cuffs. Blouses with pussycat bows and printed fabrics were also important elements in many of his collections, and WWD credited him with showing the first midi skirt, the first ruffled blouses and the first 1940s makeup.

As WWD described his work in 1989: “Impeccably tailored suits, dresses with fitted bodices and gazar evening dresses became his trademark.” He was a living link to the golden age of French couture, when the collection that really mattered was the made-to-order one registered with the Chambre Syndicale.

Bohan attended the Lycee Lakanel in Sceaux, then started working in a bank at his father’s insistence. But he hated it, and he used to spend his lunch hours attending fashion shows.

He began his design career by working as an assistant at Robert Piguet and Edward Molyneaux. He designed the couture collection of Madeline de Rauch and also worked secretly for two New York design houses, Adele Simpson and Originala.

Bohan opened his own couture house, which lasted for only one season, failing because it was under-financed. He told People magazine in 1978 that this event “marked me. It was an enormous deception.”

It also made him decide never again to design under his own name. Bohan designed the couture collection at Jean Patou from 1954 to 1958, then designed Christian Dior London from 1958 to 1960.

He came by his most famous gig in an unusual way. Bohan was asked to succeed Yves Saint Laurent when Saint Laurent was drafted into the French military. The word among fashion insiders was that the house of Dior had only allowed Saint Laurent to be conscripted because it was appalled by his then-controversial beatnik couture collection for fall 1960 — which included fur-trimmed crocodile-motif leather motorcycle jackets and short skirts. At the time it scandalized Dior’s more conservative couture customers, but it’s now considered one of the most important collections in fashion history.

Saint Laurent’s stint in the military was very brief; after six weeks, he had a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized. French law prevented employers from firing employees who were doing their compulsory military service. The house of Dior, however, did exactly that — at least according to a lawsuit filed by Saint Laurent and his combative business and occasional life partner Pierre Bergé. They used the settlement they won to launch their own house, which became legendary in its own right.

Saint Laurent’s arrival at Dior in 1957 upon the death of Christian Dior was a rock star moment, with crowds lining up in the streets after his first show to applaud the young designer. Before he showed his first collection for the house in Paris, Bohan told WWD in 2007, “Most people had their knives out. People were licking their lips. They were waiting for me to fall on my face. Nobody expected a success.”

But what he called “the Slim Look” was a success, marked by flaring shapes and shirtdresses, and American retailers swarmed him. Elizabeth Taylor ordered 12 dresses.

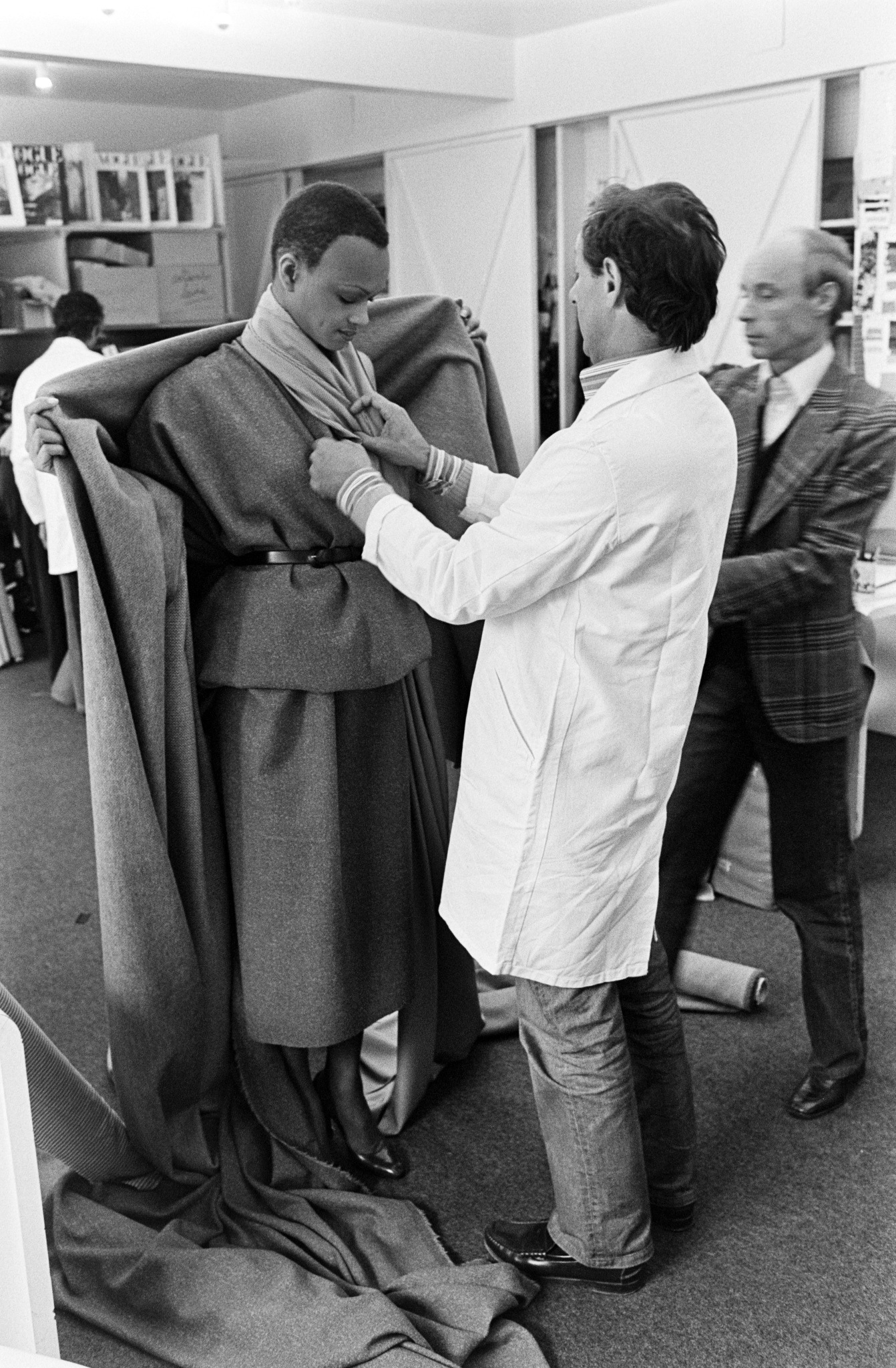

Marc Bohan poses for portraits in his apartment on July 3, 1970 in Paris.

Reginald Gray/WWD

In 2007, Bohan described to WWD what he had decided to do with the collection: “I wanted something that was easy,” he said. “I liked Jackie Kennedy’s style, with the T-shirt blouses with a short skirt, or the little cocktail dress. I wasn’t inventing the wheel. I was against anything rigid.”

He said he was careful to imitate neither of his two predecessors, Dior and Saint Laurent.

Bohan became known for what WWD used to call “money-in-the-bank” clothes for retailers and flattering couture looks for rich women. WWD wrote at the beginning of his career, “His strength is his self-effacement and his concern is with the woman and the way she looks and feels in his clothes.”

Bohan himself said at the time, “My style makes itself felt slowly via the woman. She must feel happy in her clothes. A woman wants to be paid compliments. She wants to please. And that is the way I feel about creating clothes.”

“I prefer classic looks with a little something extra,” he once said.

His 1966 fall couture collection inspired by the film “Dr. Zhivago,” with its beautiful long coats, calf-length dresses and high boots, was a particular hit. WWD wrote at the time, “His heroines are out of Evelyn Waugh, Boris Pasternak, some early Noel Coward, Michael Arlen — and I even saw a bit of Edith Sitwell.”

I am not in the business of pushing myself or my name. The people who matter know what I have done.”

Marc Bohan

Another notable collection was his Gigi-inspired one for Dior couture in fall 1977, which featured short dresses with Pierrot details inspired by Colette’s indelible heroine. ”They’re all like the girls Colette wrote about. Innocent, timid and, at the same time, romantic and a little bit naughty,” he said at the time.

His fall Dior couture line for 1985 also won plaudits. WWD described its clothes as “provocative in a light-hearted, saucy way,” including form-fitting dresses and suits.

The designer who, as a young man, resembled the French film star Jean-Pierre Léaud, was always regarded as one of the best-dressed men in Paris. He drove a red English sports car, but his manner was low key. He was a meticulous man with a hair never out of place and a suit always perfectly just-so. His face as he aged could often appear lugubrious in a way only a French person’s can, with rarely a smile and even then only a small one. Friends described Bohan as always reserved and often somewhat downbeat — again, in the typically French way, a citizenry whose attitude toward life can border on the woe-is-me.

As Bohan once put it, “I am not in the business of pushing myself or my name. The people who matter know what I have done.”

One of the things he did was to help to make designer clothes for children a major phenomenon. He didn’t invent it; credit for that goes to Jeanne Lanvin, who, before founding her own couture house, designed childrenswear.

Bohan’s daughter Marie-Anne was the first model for Dior childrenswear, and there are touching pictures of her as a child with her father in which she’s wearing his designs. He also created a series of outfits for Elizabeth Taylor, which were mirrored in mini versions he made for her daughter, Maria Burton. Princess Grace opened the first shop for Dior childrenswear.

Bohan created many wedding dresses, but one of the most famous was made for Silvia Summerlath when she married Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf in 1976. It was a very simple silk duchesse gown with a high neck, long sleeves and train extending from the shoulders.

Another important wedding dress was Princess Caroline of Monaco’s when she married Philippe Junot in 1986. It was a full-skirted lace dress with illusion veiling.

But perhaps his most celebrated creation of all was the stylized dress and coat he created for Farah Diba Pahlavi’s coronation as shahbanou, or empress, of Iran in 1967.

“The palace was so big,” he recalled in WWD in 2007. “We went to Isfahan. We needed to find ideas for the dress. We were looking for a symbol, something appropriate, because the ceremony was symbolic. I decided on a long white imperial dress with a long train and bell sleeves, with a sleeveless coat open on each side, in green with a white mink collar, with the arms of Iran embroidered in stones on the back. She was delighted.”

When he returned to Paris, he received a copy of the Iranian coat of arms: “It came on a crumpled piece of paper that was impossible to decipher. But with Lesage, we figured it out.”

In 1989, Dior’s new owner Bernard Arnault shockingly replaced Bohan, recruiting Italian designer Gianfranco Ferré. At the time, WWD spoke to several of his licensees, including Josh Lipman, president of Cuddlecoat Inc., the Christian Dior coat license. Lipman said, “Marc Bohan will be missed. He had a particular flair with coats. He was a down-to-earth designer, easy to talk to, and he has a good eye for tailored clothing, which translates to coats.

“He had regular and numerous visits, not just to New York, but to our design room. In fact, some of our bestselling Dior coats came directly from his [Bohan’s] collection.”

Bohan was involved in the revival of the English made-to-order house Norman Hartnell, which he designed for two years. It was a bold attempt to revive one of Britain’s most fashion houses; Hartnell designed Queen Elizabeth II’s wedding dress as well as scores of others for English society.

The new owners installed Bohan in the listed Hartnell headquarters on Bruton Street and recruited an atelier to do both couture and ready-to-wear. But while Bohan’s collections got good reviews and stood out because of his savoir faire and taste, the business was continually underfunded and never really took off. It became of the casualties of the recession of the early ’90s.

Bohan was married to Dominique Gaborit from 1950 to 1962, when she died in a car accident, leaving him a single father to their daughter, Marie-Anne.

His second wife was Huguette Rinjonneau, who also predeceased him. Bohan was a confidant of French writer Francoise Sagan and he designed costumes for some of her plays. The sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle was a longtime friend. He was also close to Philippe Guibourge, his assistant at Dior, who went on to design the ready-to-wear at the house.

Bohan’s father had been a somewhat severe man who never voiced his pride in his prominent son but after his death, Bohan found a number of press clippings about him among his father’s papers, which he found moving.

In 2018, Assouline published a book by Jerome Hanover, “Bohan’s Dior: 1961 to 1989.” It was the third in a series of seven planned by the publisher about the designers at the French house. To write it, Hanover did three extensive interviews with Bohan. Among the things he learned was that, for Princess Grace, Bohan would send over a special deluxe look book each season that included fabric swatches.

The designer was one of the first people to learn that Taylor and Richard Burton’s first divorce was not holding, and that the pair would reunite. (They later remarried, then divorced again.)

In the 2007 WWD story on Bohan is another memory of the couple: “On one occasion, Bohan remembered being summoned by Taylor to London, where she was working on a film [with Burton}. ‘They were waiting for me in Pinewood Studios,’” Bohan related. “It was their wedding anniversary, and they invited me to luncheon. They were divine. They both had the most fabulous sense of humor. I was in heaven. They were fantastic together and so much in love. I’ve never seen a couple like that. It’s easy to understand why they got married twice. Their relationship was electric.”

The designer’s other interests included the opera and ballet — he designed productions for both — and collecting antiques. In 1961, for example, he did the costumes for Danielle Darrieux in Francoise Sagan’s play, “La Robe Mauve de Valentin.”

Early in his career, he bought a farmhouse in Burgundy, and he eventually retired there, buying a beautiful vintage town house.

“Country living is different from the United States,” Bohan explained to WWD not long after he bought the house. “You’re not forced into a weekend community. Nobody knocks on your gate in Meau with a pitcher of Bloody Marys. No groggy Sunday brunches.”

Over the years, Bohan received a number of accolades. In 1963, he was given the Sports Illustrated Designer of the Year award and an award from the Schiffli Lace and Embroidery Institute. He was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1979. Monaco gave him the Ordre de Saint Charles. In 1985, he won an illustration prize for his costumes for an opera by Henze, “Boulevard Solitude.”

In 2009, the Dior Museum in Granville on the Normandy coast put on a show, “Dior: The Bohan Years,” which featured looks from Bohan’s nearly 30-year career at Dior, including many he created for Princess Grace, which were borrowed from Monaco. Among them was the famous “La Bayadere” dress Bohan did for the spring 1967 Dior couture collection, featuring yellow and orange chiffon with matching stones and other embellishments.

After the Assouline book was published, Hanover said he hopes that Bohan will be remembered “not as a man of one style, but as a man of style. When you see shows in 2018, you see Bohan everywhere,” he explained, saying designers are becoming more interested in the chic ’60s style epitomized by Bohan at Dior. “You see [his work] in Prada, Raf Simons, Hermès — I think it will help fashion to remember that Marc Bohan really designed the ’60s.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.