HIP-HOP WAS BORN IN THE BRONX in the summer of 1973. To celebrate the music’s 50th anniversary, “Rolling Stone” will be publishing a series of features, historical pieces, op-eds, and lists throughout this year.

MC Lyte has been grinding since 1987, first as powerhouse MC during rap’s golden age, then as an actor, radio personality, and entrepreneur, among other pursuits. With the new Netflix docuseries, Ladies First: A Story of Women in Hip-Hop, which is out today, she got to try out a new role: executive producer. Lyte is confident that Ladies First — which tells hers and other crucial stories — will help ensure that no one else sleeps on the culture’s large-and-in-charge women. “It was very important to [release Ladies First] in the 50th year of hip-hop,” she says. “I think the documentary is great in terms of representation and eras. You know, having Sha-Rock is everything. That’s, like, the first female MC to ever do it.”

Known for her booming tone and tense pocket, Lyte (born Lana Moorer) dropped gems like her 1988 hit, “Paper Thin,” and 1993’s “Ruffneck,” which made history as the first single by a woman rapper to go gold. She was among the first rappers to release a conscious hymn with 1987’s cautionary fable, “I Cram to Understand U (Sam),” which described the misadventures of an addict named Sam. A year later, Lyte appeared as a newscaster magnifying Wall Street’s drug problems in Public Enemy’s urgent “Night of the Living Baseheads” video. Her verse on the 1989 anti-violence hit “Self Destruction” is timeless; when Da Brat rhymes it word for word in Ladies First, it’s one of the series’ most thrilling moments.

Lyte’s zeitgeist-grabbing exploits helped position her comfortably in Hollywood. Leveling up in each era, from the fierce Eighties to the flossy Nineties, she earned hits with the spunky “Keep On, Keepin’ On” and the Puffy-helmed “Cold Rock a Party (Remix)” and appeared in everything from sitcoms to blockbusters. And somewhere between crashing Moesha episodes and the 2017 film Girls Trip, Lyte produced a star-studded Centric doc about the life of Heavy D.

When it was time to celebrate strong women in hip-hop, Lyte felt (dutifully) liberated. “I can tell you I had been in many a room a few years prior to the pandemic trying to get a women’s documentary done,” she said. “This was wonderful to be able to participate in, in many ways. It was time.”

The film is bracing and insightful, giving viewers an upbeat history lesson starting with the Bronx legend Sha-Rock. The humble beginnings, moments of triumph, and righteous rages (against haters, the patriarchy, and more) amount to a staunch portrait of venerable women, from Lyte to Yo Yo to Tierra Whack. “It was important to have women then, and it’s important to have women now,” said Lyte. “And I think that the documentary shows the array of women that have been able to rock a crowd and contribute to the genre.”

You’re an executive producer on Ladies First. How did you become involved in the production?

Just simply — “hey, I’m MC Lyte.” No [laughs]. What was wonderful is I just wanted to be able to be an aid. In a production of this kind, you wanna make sure that you include all folks that need to be there. And, you know, quite frankly, there are those who did not make an appearance [in the film], but that doesn’t mean they didn’t go without invitation. When you’re working on a production of this nature, you kinda have to get who you can, and also, you’ve got time constraints. So things can sort of close up before everyone can participate. But I think we have a great level of participation from women in hip-hop in front of the camera and behind. I think the day has come when everyone finally understands how important it is to have women rockin’ on the mic.

What are some of your favorite memories from the Eighties?

A lot of the locations. I always hear about [Sedgwick Avenue] and how important to hip-hop that place is. For me, Latin Quarter was very important. Not only was it the place many acts had their first time on stage, it was also a place where rappers, DJs, and the community were able to exist in one space. It was a place where DJ Red Alert would be on turntables every Tuesday and Friday. Paradise, who ran the club, made sure rappers were treated not only fairly, but great.

That time was very important for me, along with a lot of the other places that we were able to go and party and listen to new music and see new artists. Union Square was one of those places. And, of course, you had the Red Parrot and the Roxy, and many roller rinks across the Tri-State area that made hip-hop available: not just a DJ playing, but also seeing performers. They had clubs uptown. They had the Zodiac and the Zanzibar and the Rooftop and the . . . I mean, it just goes on.

You mentioned the roller rink. On “I Cram to Understand U (Sam),” you shouted out . . was it Empire Skating Rink?

Uh-huh. Empire Roller Rink. And then there was Utica Roller Rink. And then there was Skate Key. There were quite a few around during that time — the Eighties and Nineties — that were really great for being able to commune with fellow hip-hoppers.

You must have had to deal with a lot of nonsense in a male-dominated industry. How difficult was it?

You know, while I was living it and in it … no, I didn’t feel it at all. It wasn’t until I was older. You know how it is [laughs], when you’re a kid, you’re just playing with all kids until somebody tells you that that kid is different from you, or that kid has a different color skin? I think I was oblivious. I was 16 when I came into it. It wasn’t until many years later where my manager said, “You know it was difficult.” And I was like, “Really?” [Laughs.]

It was almost shocking to me because I was allowed to just do my craft, show up and participate in hip-hop, an art form, a genre that I loved. And so, I wasn’t burdened with, “this isn’t gonna work,” or, “this is difficult.” What I do remember is being told that promoters didn’t wanna pay us what we were owed. I was told by management that this rapper didn’t wanna go on before me, although I had had many songs out, and my status would say I should go on at a certain point within the show. But there might have been a few male rappers that didn’t wanna go on before MC Lyte. Needless to say, I never let any of it get to me.

“I Cram to Understand U (Sam)” is a classic. It’s almost low-key conscious, back when that term actually meant something. You should probably get more credit for that.

Well, thank you very much. It was all the way conscious as far as I was concerned ’cause I was out to send a message to my peers that drugs shouldn’t be tolerated in any form and in any way. You should try to stay away from drugs and from people who sell it, take it, play with it, whatever it is. You know, in the Eighties was the crack epidemic. And in Harlem was heroin, and Brooklyn was crack. And I just wanted to tell the generation I was a part of to stay away from it. So, that was very on point to be conscious.

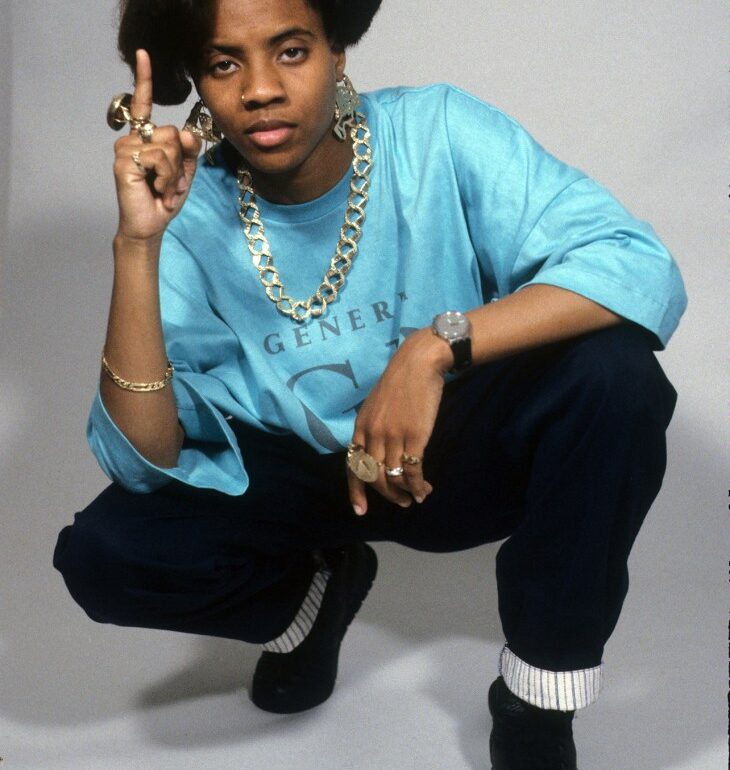

Lyte in 1989

Al Pereira/Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives

I put it in the story form, just as I did with “Poor Georgie” and “Not Wit’ a Dealer” and “Eyes Are the Soul,” and many songs that I have on the multitude of albums that exist out there that I was blessed enough to release. But, yeah, it all started with “I Cram to Understand U.”

Do you think your social commentary on “I Cram to Understand U” inspired KRS-One to reach out to you to appear on “Self Destruction,” the single by the Stop the Violence Movement?

You know, that’s interesting. I never asked him. There were many songs that came out after “I Cram to Understand U” that could have sparked off the invitation to participate.

As a matter of fact, we talked about just the Movement, as of late — KRS-One and I, with Chuck D. Chuck had me come out for “Night of the Living Baseheads,” where I played a news commentator that literally takes the news cameras into a boardroom where guys are doing drugs, which was sort of outlandish. I don’t remember which one came first. I would have to look [laughs]…I would have to Wikipedia it to see. But I think they both were in ’89. Maybe one sparked the other, or not. I just was excited to be a part of it.

You’re known first and foremost as a straight-up spitter. Everything from “Cha Cha Cha” to “Paper Thin.” But you’ve always managed to upgrade in every era. Does your ability to stay so relevant have something to do with your achievements in TV and film today?

It’s interesting how much the producer actually dictates where hip-hop goes, tonally, right? And, you know, I had the great fortune of having a great A&R. Merlin Bobb at Atlantic Records would let me play, for the most part, then at the end of every album, he’d say, “OK. Now we gotta go to work.” [Laughs.] And then he’d send me to what we identify as the superproducer. Many times over, I was in the right place at the right time.

When it came time to go to Teddy Riley, I was able to get “Ruffneck.” When I went to Jermaine Dupri, I was able to get “Keep On, Keepin’ On.” When I went to Puffy, I got “Cold Rock a Party.” And the truth is, in ’98, I had the Neptunes before anybody knew who they were.

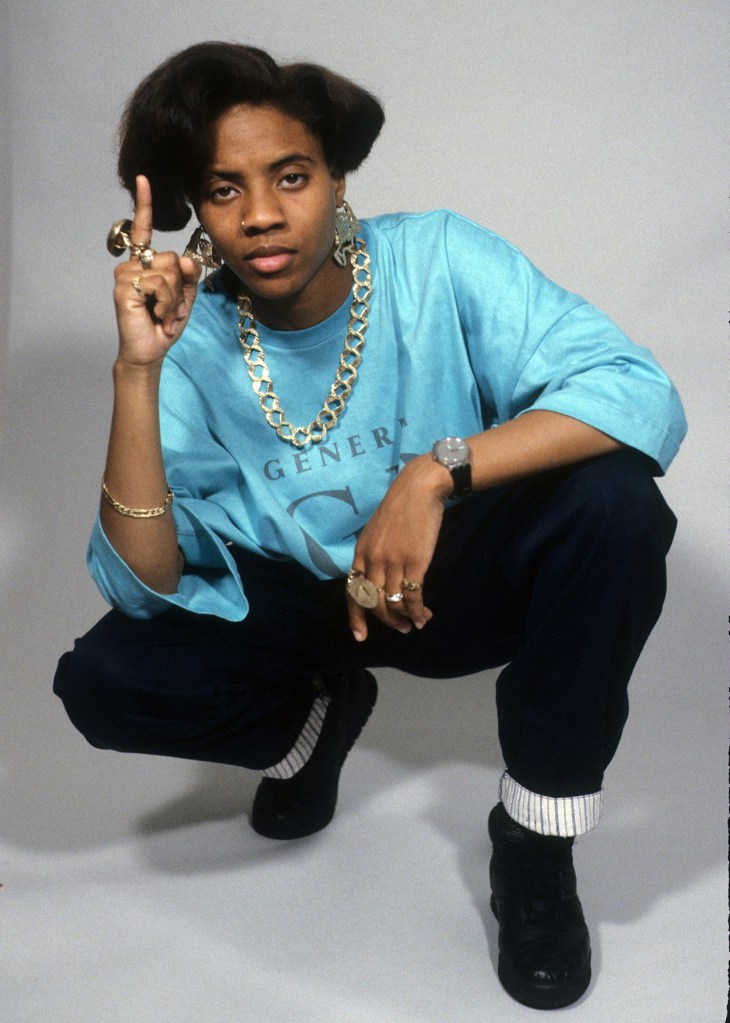

Lyte (middle) shooting the video for “Cha Cha Cha” on New York’s Randall’s Island, August 28, 1989

Al Pereira/Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives

All of that being said, in the midst of us having great songs and great notoriety on the chart, my first manager said to me, “We need to make your name relevant even when you don’t have a hit record.” And that gave me permission to begin to dream again about all of the things that I wanted to do prior to hip-hop. I heard Carol Ford on New York Radio; I wanted to do radio way before I wanted to rap. I was enrolled to attend Norfolk State University in the fall of ’88. But before I could even get to there, I had a major record deal with Atlantic Records and Sylvia Rhone. So, I was able to then go into using my voice. “OK. Let me go to voiceover coaching.”

I wanted to act when I saw Tootie on Facts of Life. When I moved to Los Angeles, my record label was like, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m pursuing acting.” “No, you need to be here in New York on the city streets . . . so people can see you.” And I declined. I said, “No, I’ve done that. It’s time for me to build upon what’s gonna be next.”

I’ve had the opportunity to do many things. Case and point, Ladies First is the first time I’ve been included as an executive producer in a project that I am very well versed and knowledgeable about. And I think if there was such a project to be involved in, this is it.

You mentioned the voiceover work. Hearing MC Lyte announcing AT&T plans is probably the ultimate example of what Biggie had in mind when he said, “You never thought that hip-hop would take it this far.”

It still blows my mind. To be able to do the Super Bowl and NBA conferences, and the Grammys and the BET Awards and the Emmys and . . . yes, your AT&T plan [laughs]. It just goes to show that you have fans in great places.

Could we see MC Lyte doing voiceover work for the next big animated film, getting that Eddie Murphy money in the next Lion King?

[Laughs.] From your mouth to God’s ears, you know? I’m open for it all.

What do you think will be the biggest takeaway from Ladies First?

That women are unified. And that we also respect one another. And we also understand that this is a business. And although we are celebrated in within this documentary as women in hip-hop, we also are celebrated for our individuality. I think that’s important.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.