“And instead of what he was doing to them,” she says of the song today, sitting at Kimmie’s Kitchin inside Two Star Market, “they were doing to him.”

In “The Real Freaky Tales,” Too Short is objectified. He’s used for cunnilingus by the women, and then pimped out by them. He’s thrown in a car trunk and driven to a house full of women who force him into sexually pleasing them at gunpoint. Against his will, he’s violated by a foreign object — and comes to enjoy it. He stops being a rapper and becomes a streetwalker. In the hyper-masculine world of Oakland pimp rap, this was a wholesale murder.

What did Too Short think when he heard it? “He laughed! When he heard the full song, he laughed,” says Kimmie Fresh. “And then he said, ‘We gon’ make some money.’”

Even in the mid-’80s, Short knew the mutual benefit to be had from a public rap beef. He invited Kimmie to open for him at the Turf Club, at Golden Gate Fields in Albany, she recalls, “and the crowd just went crazy.” While he worked out a major-label deal for her with Jive Records, she recorded songs with affiliates of his Dangerous Music label at Different Fur studios in San Francisco. At the time, no female rapper in the Bay Area had ever released a full album.

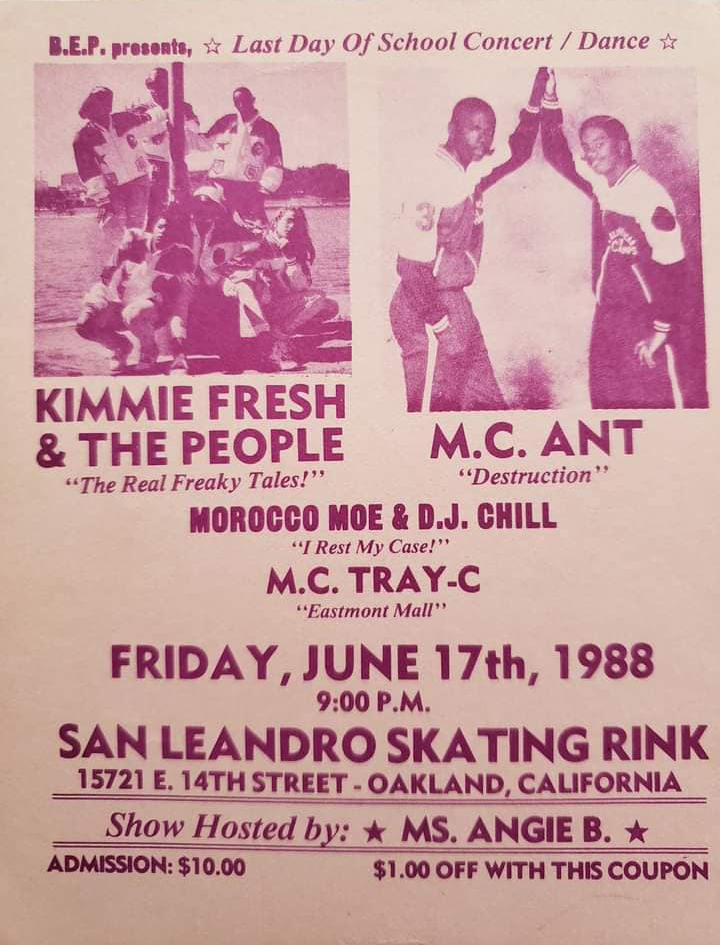

(Larry Henderson/75 Girls Records)

And then she got impatient. As the months dragged on, she ran into Dean Hodges, owner of the small local label 75 Girls, which his top-selling artist Too Short had just left. Hodges was excited at the idea of releasing a Too Short diss track, and having already started working with another young female rapper from Oakland named Cassidine, he offered to pay to re-record the songs and release a Kimmie Fresh album with the quickness.

At her food counter, Kimmie Fresh pulls up video footage on her iPad, rescued from a VHS tape found at a garage sale, which captures the excitement of her 75 Girls deal. She and her friends shoot photos for the album at Lake Merritt and Eastmont Mall; MC Hammer even stops by and lends his support. They rehearse in her small living room on 75th Avenue, dancing and rapping in formation. They hold up a banner in the street advertising their four-city tour in the south opening for Morris Day and Pebbles, giddy with disbelief.

One person, though, didn’t appear too happy. On the back cover of his next LP, Too Short concluded his liner notes with a direct message: “Kimmie Fresh, THANKS FOR NOTHING. Biiiiiiiitch!!!”

Pimp Rap and the Crack Epidemic

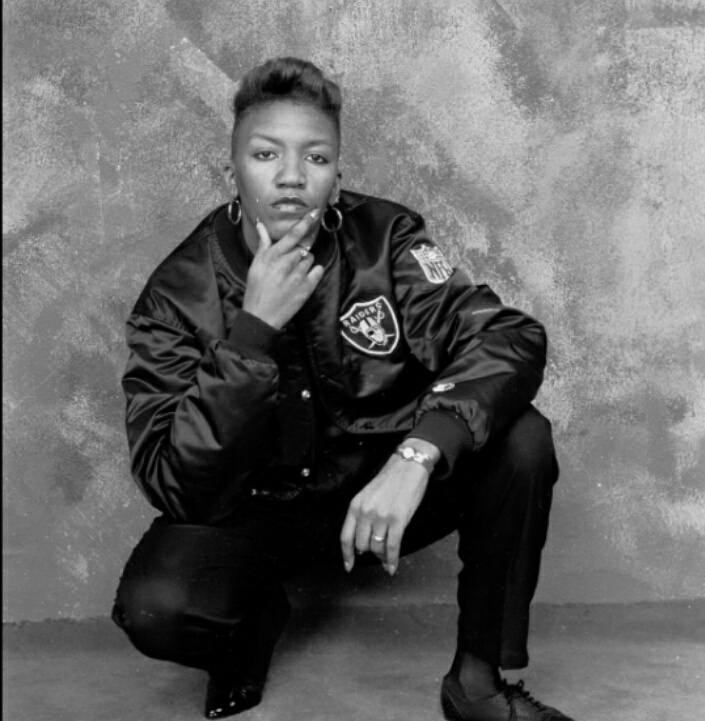

Remember the power of a public rap beef? These days, Short and Kimmie are cool, and see each other regularly. Part of it may be because Kimmie Fresh was more than a novelty, but a genuinely fierce rapper.

If you can find a copy of The Real Freaky Tales — now a collectors’ item that has sold for as much as $300 — you’ll hear a vivid portrait of Oakland in the 1980s. “I Love My Microphone” is a high-speed litany of boasts. “Tear the Roof Off” and “The Crowd Be Lovin’ Me” take on challenges and pickup attempts from men, shouting out Jody Watley, Janet Jackson and women in her own crew from 75th Avenue.

Then there’s “Don’t Let That Be the Reason,” which chronicles the rise and fall of a wealthy player who gets hooked on crack and lands in jail. The judge asks him to snitch, but he refuses, even though his friends won’t bail him out. After prison, he loses everything, and watches old associates walk by while he sleeps in the gutter.

As we talk, Kimmie Fresh spontaneously raps these songs at the table, still in possession of her skills. The songs are close to her, after all: “Don’t Let That Be the Reason” was a composite sketch of friends and family in East Oakland who fell victim to the crack epidemic, Kimmie says, nodding in reflection.

“That was many people I knew,” she says. “Many, many people I knew.”

Kimmie wasn’t the only young woman in the 1980s Bay Area rapping explicitly about sex. Cassidine’s “Secret Weapon” was a graphic salute to prostitutes, some just 16 years old, working the strip on E. 14th Street, and a rebuke to the men who prey on them. Under the group name Danger Zone, Barbie and N-Tice (who had been on “The Real Freaky Tales”) had the song “Jailbait,” a warning about men to “all you girls out there who are under 18.”

Both serve as a balance to the male-centric Bay Area pimp rap of the 1980s from Too Short and Magic Mike and Calvin T. Kimmie herself came up around a lot of pimps: she mentions Frank the Bank, Gangsta Brown, even her own brothers. They all told her the same thing: “Don’t ever let a man treat you like we treat these hoes.”

“So I’ve always been strong,” Kimmie says, matter-of-factly. “They instilled that in me.”

A Life After Rap

Strong or not, life finds a way of derailing rap careers. Motherhood, especially, took up Kimmie’s time and energy. She worked various jobs: at a bank, a pawn shop, Mervyn’s, a hair salon. At one point, she spent almost a year in jail, she says, when her boyfriend was accused of murder. (“It was something that he was accused of, and he tried to say that I was there,” she says, insisting that she was not. “I got my first royalty check, and then I almost lost my life.”)

She moved to Las Vegas for a while, but after watching an ailing close friend, the rapper Tee-Mail, die of cancer back home in Oakland, “I was destroyed.” She decided to stay, sleeping on a friend’s couch, but by then, the Town had largely forgotten about Kimmie Fresh.

While D’Wayne Wiggins from Tony Toni Toné built her a cafe in his studio to start Kimmie’s Kitchin in 2019, and artists like Keak da Sneak, Mistah F.A.B. and Dru Down have all visited, the general public remains largely unaware of Kimmie Fresh. She’s often mistaken, she says, for a member of the Conscious Daughters or Oaktown’s 3.5.7. When she’s brought on stage with Too Short, the DJ inevitably plays “Don’t Fight the Feelin’,” which features Barbie and N-Tice, and she’s expected to rap their verses, as if all women rappers are interchangeable.

Her music lives exclusively in fan-ripped uploads on YouTube. It hasn’t been put on streaming, or reissued on vinyl. Getting it on Spotify is something she’s working on, but her old label boss, Dean Hodges, sold the rights to the 75 Girls catalog in the 1990s, and last Kimmie’s heard, he’s living in a West Oakland homeless encampment. She’s lost touch with Cassidine, her labelmate on 75 Girls. She doesn’t know where her old masters are, nor the recordings she made for Jive, so long ago.

Still, Kimmie is happy to still be active at her counter, cooking dishes like oxtail tacos, shrimp and grits, and chicken and waffles. She’s especially proud of her family. There are stains on her apron and a cook’s burn marks on her forearms, right near her tattoos of her four son’s names. People come in from time to time to bring her old photos of a different life, 35 years ago, from back when she says rap was better and more fun.

At the end of our interview, when presented with a cassette copy of The Real Freaky Tales, she calls across the liquor store to summon an employee.

“Angel! Come over here… have you ever seen my album?”