You might not know the name Dorothy Liebes (1897–1972), but the American textile designer and weaver was a hugely influential figure, with her work in fashion, film, transportation, and interior and industrial design helping define 20th-century taste in the U.S.

Now, she’s back in the spotlight with her first posthumous solo show—her first in more than 50 years—at New York’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. The exhibition, titled “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes,” is a celebration of the artist’s many accomplishments, her skills as a designer, and her considerable business acumen.

“Her career was so vast,” Susan Brown, associate curator and acting head of textiles at Cooper Hewitt, who co-curated the show with Alexa Griffith Winton, the museum’s manager of content and curriculum, told Artnet News. “She did so many different things, from being a Californian hand weaver, to her very prestigious commissions with important architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, to her work with fashion designers and on film sets.”

Born in Santa Rosa, California, Liebes got her start in textiles with a two-week stint at Chicago’s Hull House in the summer of 1920, taking weaving and dyeing classes. Three years later, she graduated from University of California, Berkeley, with a bachelor of arts in decorative art, architecture, and applied and textile design. (She already had a degree in art education from the State Teachers College at San Jose.)

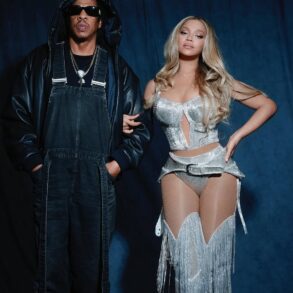

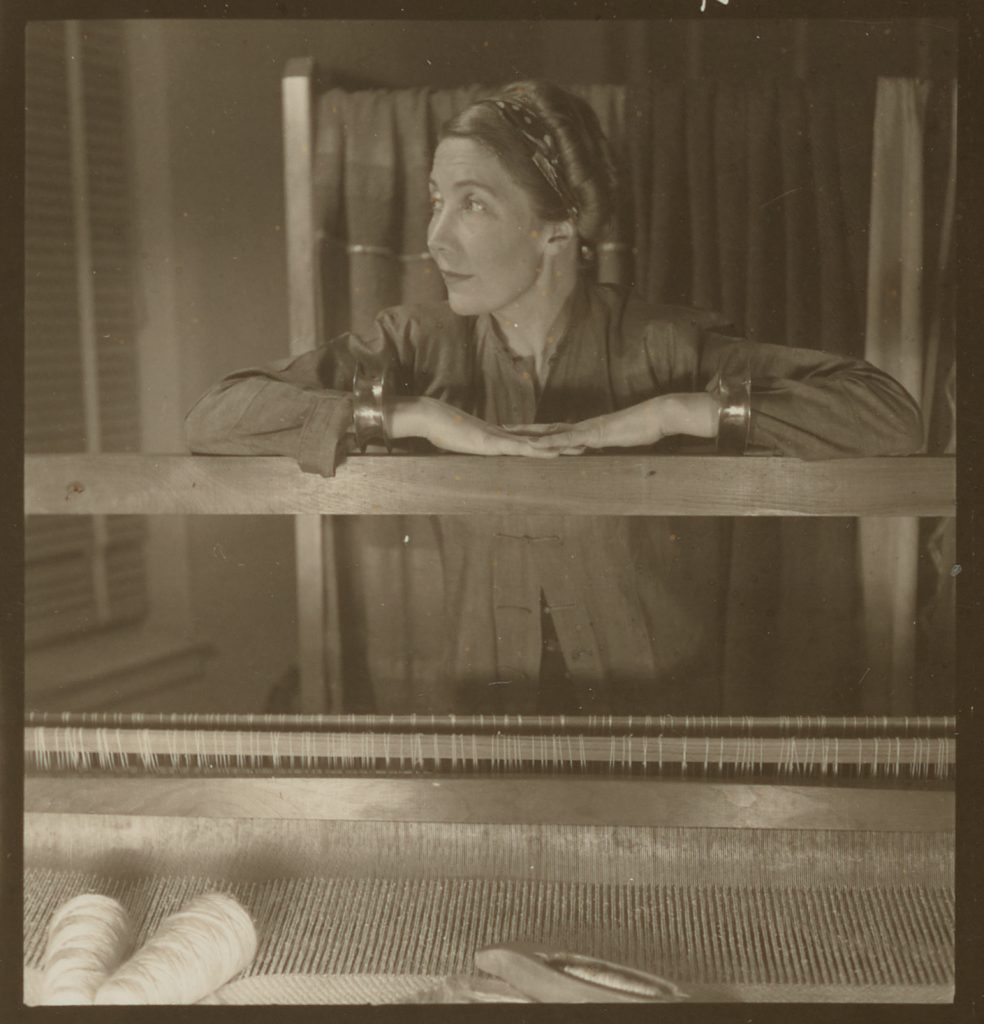

Dorothy Liebes in her Powell Street studio, San Francisco, California (1938). Photo by Louise Dahl-Wolfe, courtesy of the Dorothy Liebes Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, ©Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

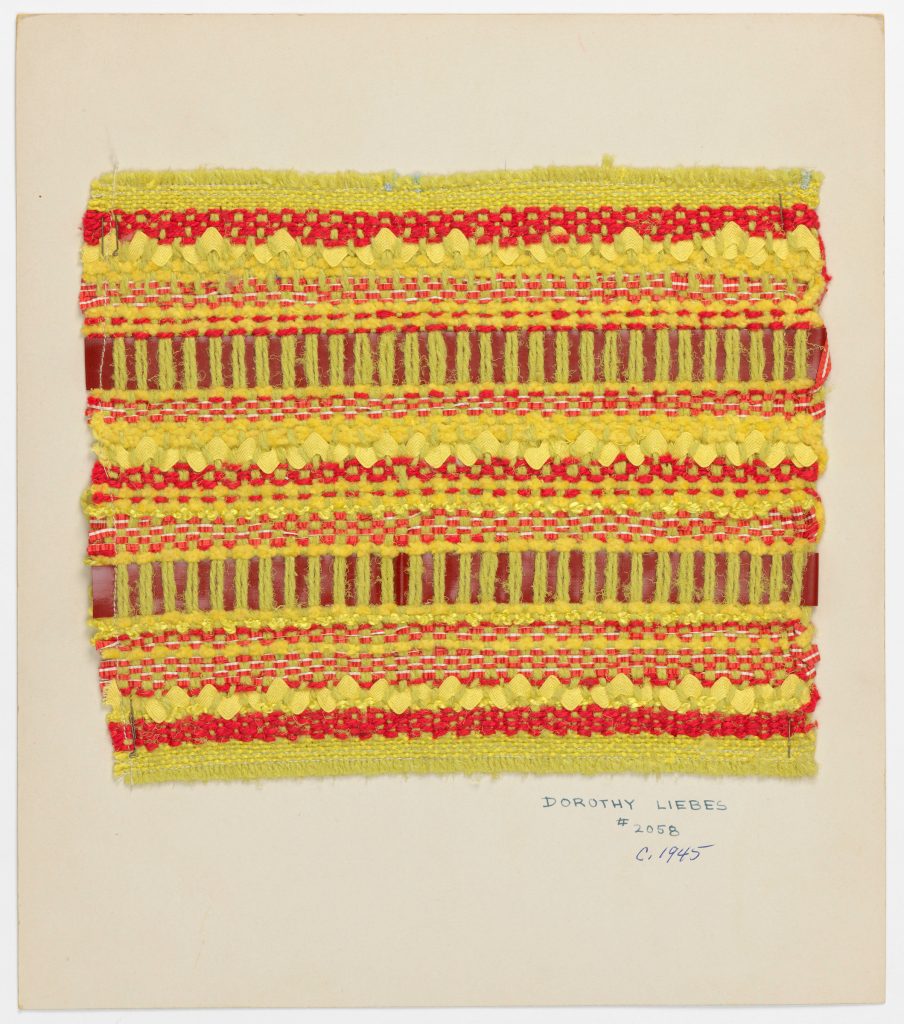

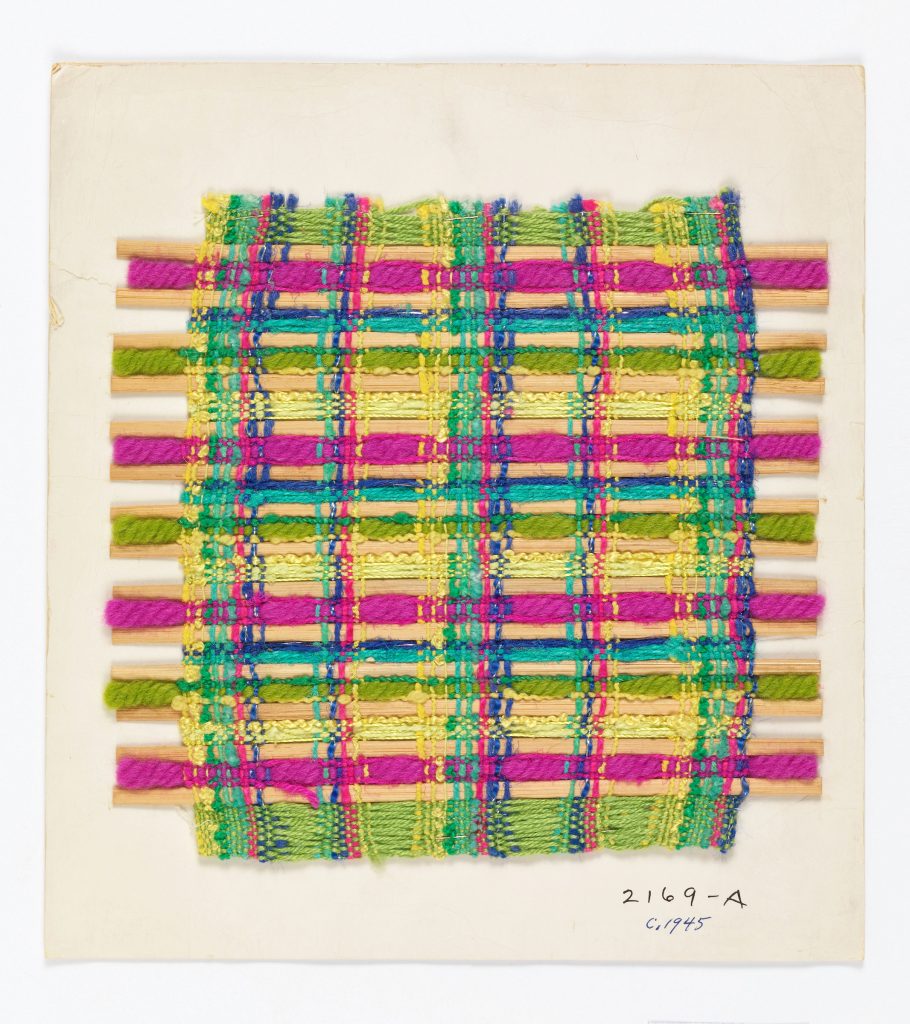

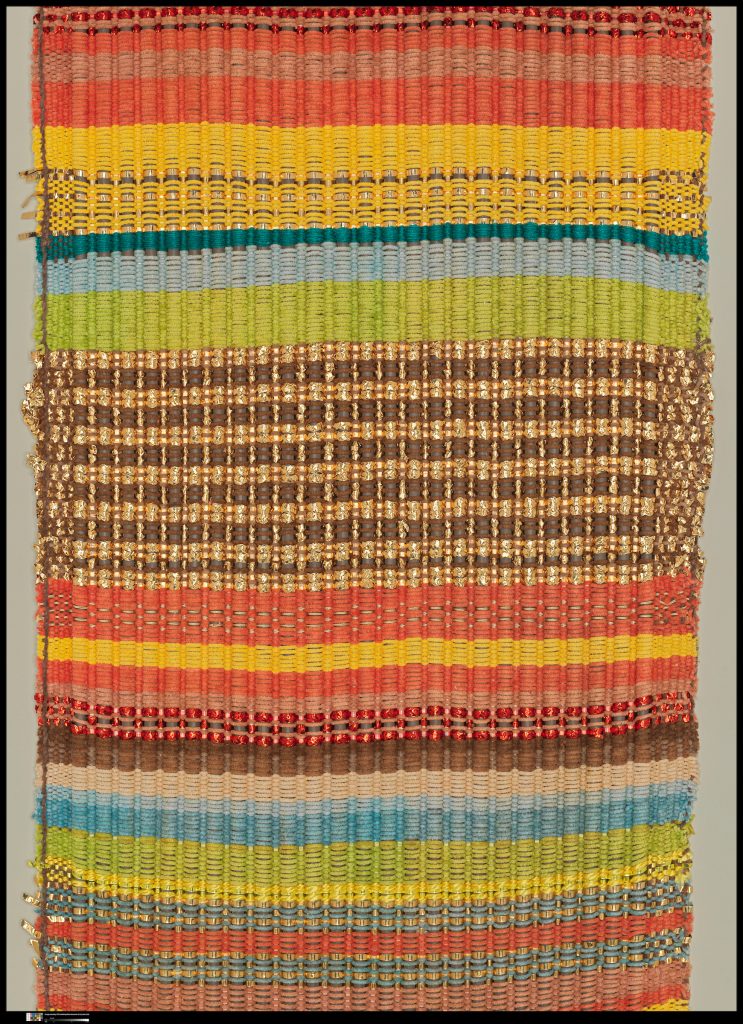

By 1928, Liebes had a commission to design draperies for the San Francisco Stock Exchange, and by 1930 she had opened the Dorothy Liebes Studio in San Francisco. Although she collaborated on major architectural projects, including designing the drapery and upholstery for the 1938 New York World’s Fair, the designer also felt it was important that the average person could experience the “Liebes Look,” as her bold blends of vibrant colors accented with shiny metallic thread came to be known.

“She was very acutely aware that her textiles were extraordinarily expensive and could only be afforded by the one percent of the one percent, and she wanted to make them more widely available,” Brown said.

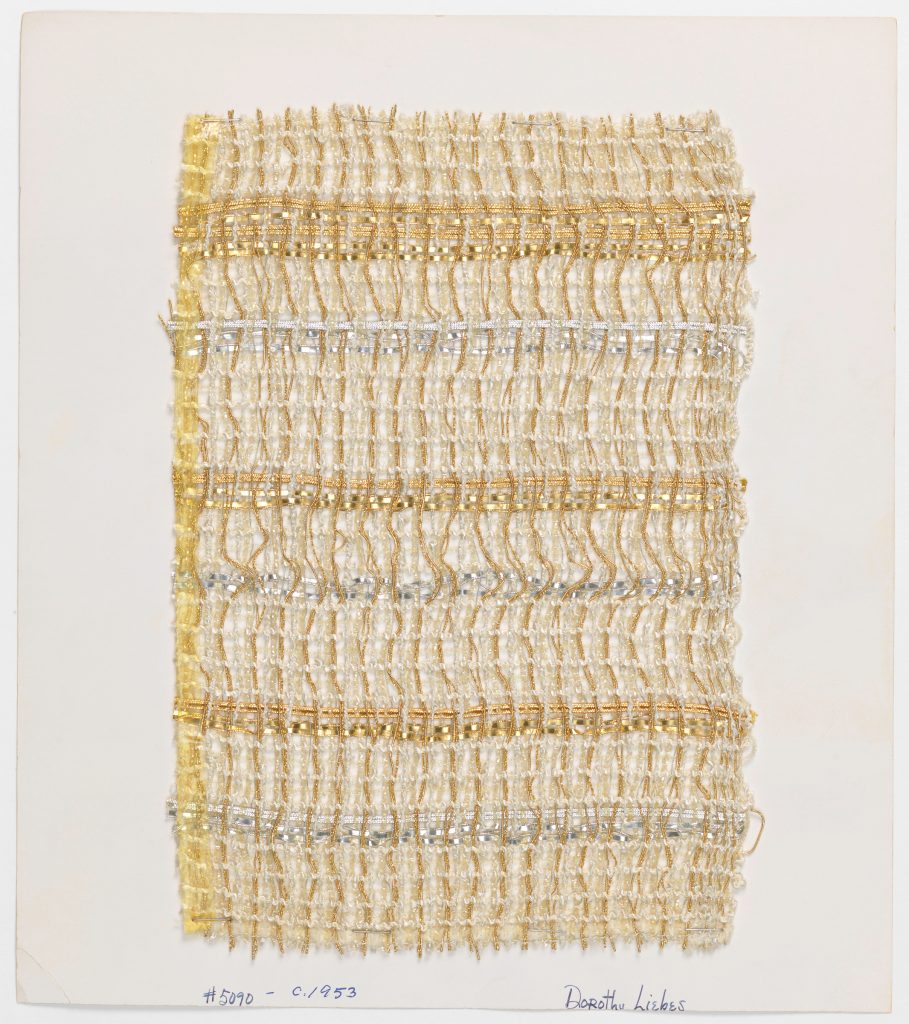

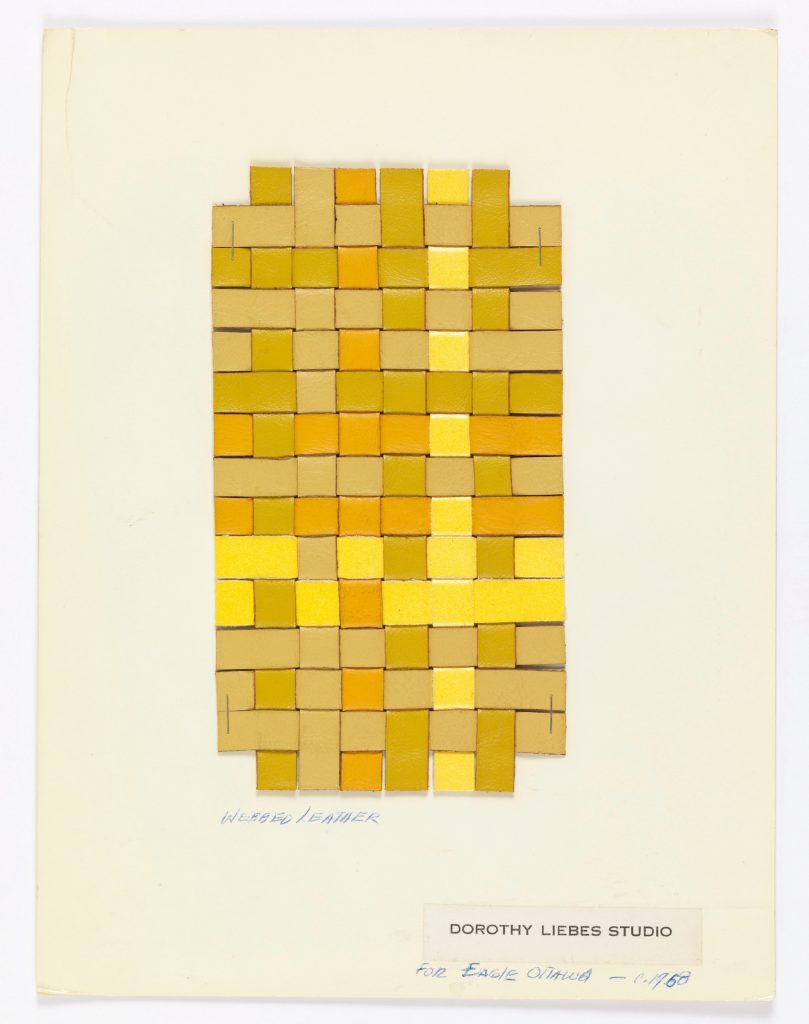

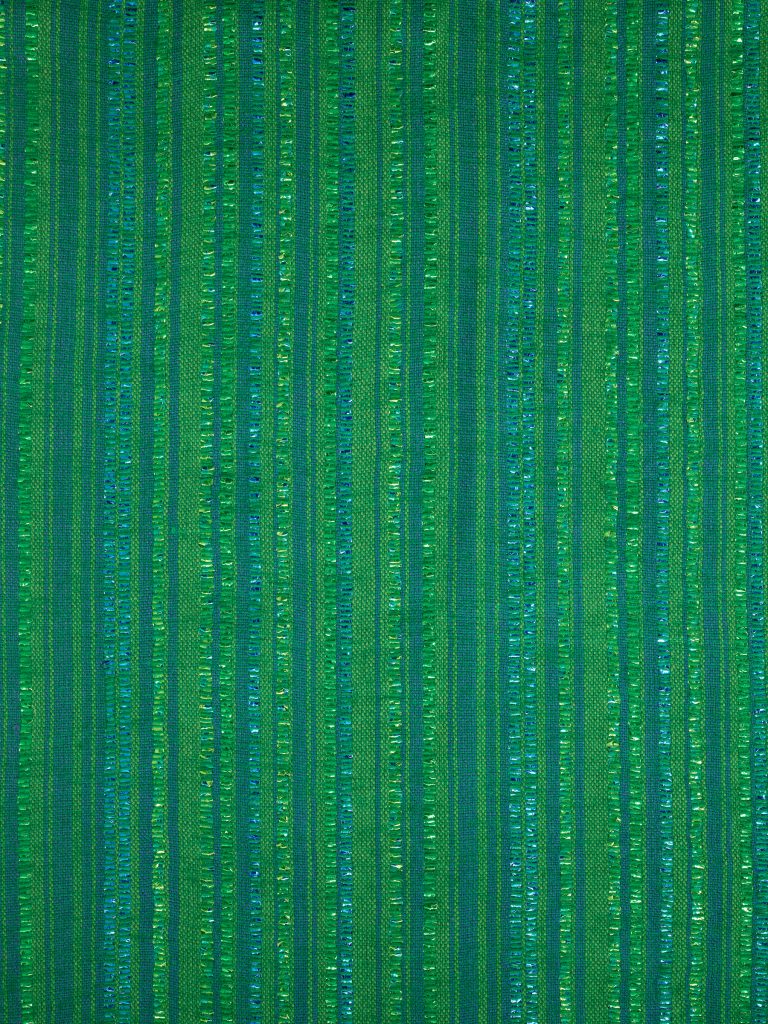

To that end, Liebes forged industry partnerships with companies like Goodall, DuPont, and Dobeckmun. (The latter were the the makers of Lurex, a synthetic metallic yarn that became a Liebes signature and that she helped expand to a wide range of colors beyond the typical gold and silver, including black and pastels.) She worked closely with manufacturers to replicate the results of her hand-weaving techniques on machine looms, helping bring her designs to the masses.

Dorothy Liebes, Mexican Plaid textile (ca. 1938). Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of the estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Photo by Matt Flynn ©Smithsonian Institution.

As a result, in the Postwar period, Liebes was able to move beyond high-profile commissions, which typically required a more restrained, subtle color palette to meet the client’s specifications, Winton said, and finally embrace “the virtuoso use of color that she was famous for.”

“The ‘Liebes Look,’ which was very frequently expressed in public spaces like nightclubs, restaurants, ballrooms, and luxury passenger liners, combined very saturated colors, often in unusual sophisticated combinations,” Brown said. “It had this textured, handwoven look with an abundant use of metallics.”

Dorothy Liebes, Sample card (ca. 1953). Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of the estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Photo by Matt Flynn, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

It was an aesthetic that continues to influence 21st-century design choices to this day—Liebes was a major proponent of decorative pillows, and of livening up a room with an unexpected pop of color.

During her lifetime, Liebes was widely recognized in the press, and exhibited her work at institutions including the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA), New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the Brooklyn Museum, which hosted her career retrospective in 1942. But, like so many women artists, her achievements quickly faded into obscurity, with the Liebes studio shuttering soon after her death, and no children to try and keep her memory alive.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Most of what was written about Liebes was in craft and women’s publications, which haven’t been widely digitized—and even when they have, photography rarely does justice to her gifted sense of color. And some of her most high-profile projects, like the New York interiors such as the Persian Room at the Plaza Hotel, the Marco Polo Club at the Waldorf Astoria, and the Usonian Exhibition House, are now almost solely associated with their male architects (Henry Dreyfuss, Donald Deskey, and Wright, respectively).

Another part of the issue was that Liebes’s relatively fragile textiles were meant to be lived with. Drapes faded in the sunlight, and upholstered furniture got damaged by cigarette smoke. Very few objects are still with us today in good condition.

Persian Room at the Plaza Hotel, New York City (1950). Interior design by Henry Dreyfuss; drapes laced with tiny electric lightbulbs designed by Dorothy Liebes. Photo courtesy of the Henry Dreyfuss Archive, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

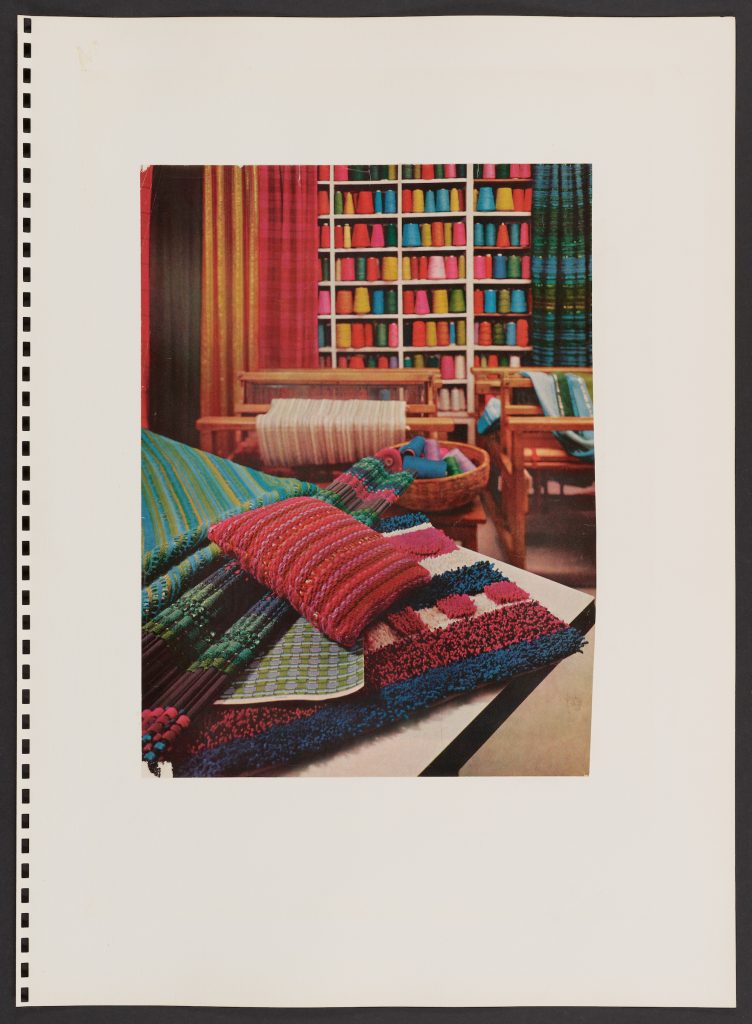

Fortunately, the Cooper Hewitt is one of a number of U.S. museums blessed with a collection of showroom samples and exhibition pieces gifted by the Liebes studio after her death. And when Brown and Griffith were organizing this exhibition, they were able to turn to the recently digitized archives of the Liebes papers—which include over 40,000 items—at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

The two believe the show—which features over 175 photographs, documents, and textiles, including clothing, furniture, and samples—has the power to reestablish Liebes’s legacy, restoring her to the pantheon of U.S. design history.

“This exhibition changes what you thought you knew about mid-century design,” Brown said. “There’s been so many monographs written about all of Dorothy Liebes’s major collaborators—Frank Lloyd Wright, Henry Dreyfuss, and Samuel Marx. Now, hopefully people will realize there’s been a very important story missing all along. Her work was very impactful and broad-reaching, and touches on so many different aspects of 20th-century design.”

See more photos of the exhibition and the works on view below.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Installation photo of “A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” at the Cooper Hewitt, New York. Photo by Elliot Goldstein, ©Smithsonian Institution.

Dorothy Liebes, Sample card, Chinese Ribbons (ca. 1947). Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of Mrs. Morris D.C. Crawford. Photo by Matt Flynn ©Smithsonian Institution.

Dorothy Liebes, Handwoven panel for the Observation Lounge of the SS United States (1952). Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of the estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Photo by Matt Flynn ©Smithsonian Institution.

Dorothy Liebes, Sample card (ca. 1945). Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of the estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Photo by Matt Flynn ©Smithsonian Institution.

Dorothy Liebes, Sample card for Eagle Ottawa Leather Corp. (1958). Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of the estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Photo by Matt Flynn ©Smithsonian Institution.

Dorothy Liebes, Sample card (1945). Collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of the estate of Dorothy Liebes Morin. Photo by Matt Flynn ©Smithsonian Institution.

Loom with shuttles at the Dorothy Liebes Studio (ca. 1947). Photo courtesy of the Dorothy Liebes Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Dorothy Liebes Studio, New York City, as photographed for House Beautiful, October 1966. Photo courtesy of the Dorothy Liebes Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Dorothy Liebes, sample for a window blind (1955). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Dorothy Liebes Design, Inc. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource New York.

Donald Deskey, armchair, (1938). Manufactured by Royal Metal Manufacturing Company; Upholstery designed by Dorothy Liebes. Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Florene M. Schoenborn. Photo courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, New York.

Dorothy Liebes, Power-loomed drapery fabric for the Persian Room, Plaza Hotel, New York City (ca. 1960). Collection of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Photo by Jacklyn Nash.

“A Dark, A Light, A Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes” is on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2 East 91st Street, New York, New York, through February 4, 2024.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.