It is unclear who was the first person to call Gil Scott-Heron the “Godfather of Rap” but when he died in 2011, at the age of 62, the epithet appeared in most obituaries. A similar honorific has been attached to the group of artists known as the Last Poets, who also began recording street poetry in New York in 1970. Public Enemy’s Chuck D made a strong case for the lineage between these poets and hip-hop to the New Yorker in 2010. “They are the roots of rap – taking a word and juxtaposing it into some sort of music,” he said. “You can go into Ginsberg and the Beat poets and Dylan, but Gil Scott-Heron is the manifestation of the modern word… In combining music with the word, from the voice on down, you follow the template he laid out.”

More like this:

– Eight forgotten forerunners of hip-hop

– America’s black national anthem

– The rappers risking the death penalty

Perhaps. In terms of tone, rhythm, content and purpose, however, what these artists were doing, along with the Watts Prophets and Nikki Giovanni, was in a different lane to the party-starting improvisations of MCs at hip-hop block parties a few years later. Back then, to “rap” just meant to talk about something important, hence Isaac Hayes’ Ike’s Rap monologues or the nom de guerre of Black Power activist H Rap Brown. Hard-edged and ultra-modern, early hip-hop owed little to jazz or poetry. Not until 1988 were MCs such as Schoolly D and the Jungle Brothers able to use new sampling technology to braid their musical DNA with Scott-Heron’s and suggest a lineage. In 2005, Kanye West brought the Last Poets back into the public eye on a track he produced for Common and concluded his most important album with a long Scott-Heron sample, using their voices to connect himself to the legacy of 1970s black consciousness.

The original street poets, however, have always been ambivalent about their relationship to hip-hop. Abiodun Oyewole of the Last Poets even sued over Notorious BIG’s flippant appropriation of their work in his track Party and Bullshit. Hailing these artists as pioneers of hip-hop is well-intentioned but it risks framing their music as merely a prologue to a much more successful movement rather than a distinctive approach to voice and rhythm, rooted in a particular place and time. “People say we started rap and hip-hop, but what we really got going is poetry,” Oyewole told the Guardian in 2018. “We put poetry on blast.”

The Big Bang occurred on 19 May 1968, when three young poets came together as the Last Poets in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park. Held to mark the birthday of the late Malcolm X, the event took place six weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King, in a period of crisis for the civil rights movement. “When they killed Dr King, all bets were off,” recalled Oyewole, the only member of the confusingly unstable line-up to survive from that first show to their debut album two years later.

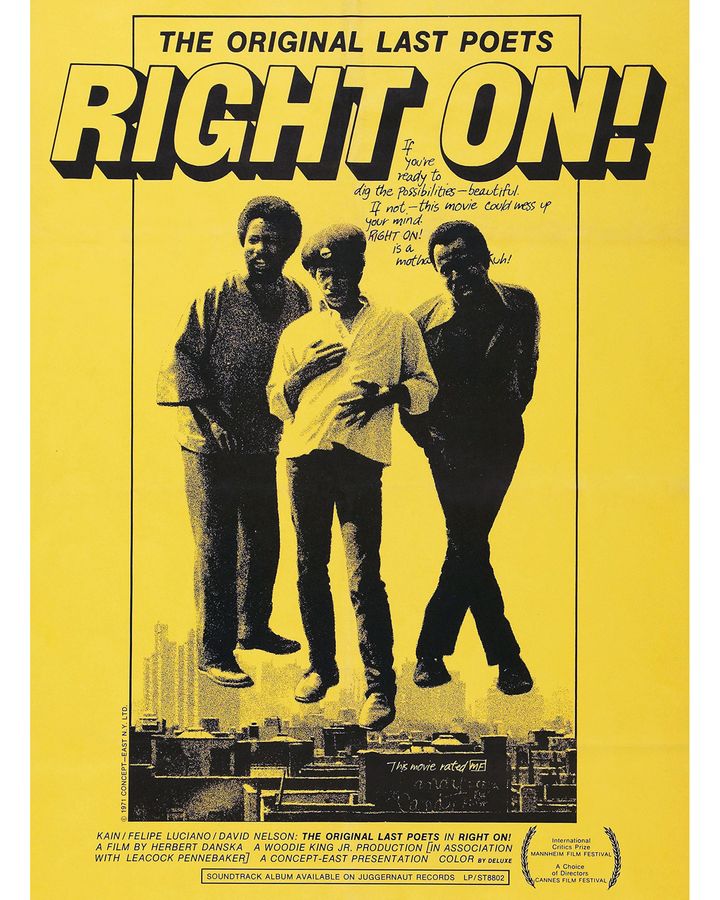

The Last Poets came together in 1968 (the 71 lineup shown here) at a birthday celebration for the late Malcolm X (Credit: Getty Images)

The Last Poets were an uncompromisingly radical proposition, fusing the militancy of jazz musicians such as Archie Shepp with poet Amiri Baraka’s call for “poems that kill, assassin poems”. Pairing stark, declamatory vocals with Afro-Cuban conga rhythms, tracks like When the Revolution Comes denounced both white America and passive black people who were unprepared for the uprising that the Last Poets unquestioningly believed was imminent. The impression that the band was the unofficial musical wing of the Black Panthers was soon confirmed when Oyewole was jailed for an armed robbery on some Ku Klux Klansmen.

Gil Scott-Heron was studying at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania when the Last Poets performed there in 1969. According to Oyewole, he came backstage and said, “Listen, can I start a group like you guys?” Scott-Heron was a prodigiously talented poet and novelist who wanted to add music to the mix. “The first thing we thought about was congas, à la the Last Poets,” his fellow student and long-time musical collaborator Brian Jackson recalled.

The sleeve of Scott-Heron’s debut album, 1970’s Small Talk on 125th and Lenox, pitched him as a kindred spirit: “Gil Scott-Heron takes you Inside Black… His is the voice of the new black man, rebellious and proud, demanding to be heard, announcing his destiny: ‘I AM COMING!'” The righteous poetry and nervy congas led some listeners to assume that he was a new member of the Last Poets, but he was deeply sceptical of revolutionary sloganeering.

Gil Scott-Heron and The Last Poets have been described as the “Godfathers of Rap” (Credit: Getty Images)

Scott-Heron’stone was sly, ironic, wickedly playful and clinically precise. Whitey on the Moon contrasted Apollo 11 mania with Harlem’s struggles in 89 devastating seconds. The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, his signature song, was a satirical masterpiece, bulging with strange little jokes and pop-culture references. “People would try and argue that it was this militant message,” he told the Daily Telegraph in 2010, “but just how militant can you really be when you’re saying, ‘The revolution will not make you look five pounds thinner’?” His next album, Pieces of a Man, was fluid, funky and mellifluously sung. Only the rerecorded The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, fattened up with a much-sampled groove, qualified as street poetry. From then on, long, hilarious political “raps” such as H2OGate Blues (Nixon) and B-Movie (Reagan) would be in the minority.

‘Politically dangerous’

The one street poet who has actively sought the mantle of rap precursor is Amde Hamilton, the sole surviving member of Los Angeles’ Watts Prophets. When I interviewed him in 2009, he pointed to the title of the group’s 1971 debut Rappin’ Black in a White World: “We’re the ones who named the art form. That’s what’s so painful about what happened to us, being written out of history. We knew what we were doing – we were poets but we called it rapping. And that’s where the music industry got the name rap music.” The etymology is not that direct, but you can see his point.

Hamilton, Otis O’Solomon and Richard Dedeaux emerged from the Watts Writers Workshop in 1967, a year before the Last Poets. “We didn’t know them and they didn’t know us,” Hamilton told me. “We didn’t copy them and they didn’t copy us.” He was suspicious of the Black Panthers and radicalism in general: “We weren’t trying to be revolutionaries; we were trying to save our communities.” Nikki Giovanni, a New York poet who released her gospel-backed debut album Truth Is on Its Way in 1971, brought a female perspective to street poetry on tracks like Woman Poem and Ego Tripping.

New York poet Nikki Giovanni, who released her debut Truth is on Its Way in 1971, brought a female perspective to street poetry (Credit: Getty Images)

One way in which the street poets anticipated hip-hop is that they were deemed politically dangerous. Unlike NWA or Eminem, they lacked the commercial impact to inspire boycotts and White House denunciations (“We didn’t make a dime,” said Hamilton) but they certainly attracted hostile attention in the shadows. “We were on President Nixon’s list, the defence department list, the national security list,” Last Poet Umar Bin Hassan told me in 2010. “It kind of blew my mind.” In 1973, the Watts Writers Workshop was burned to the ground by a trusted employee who turned out to be an FBI infiltrator.

Looking back, Hamilton told me that the street poets shared a common impulse with hip-hop: “We were vomiting. We had a stomach full of pain. We were expressing what we thought, what we felt, what our people thought, what they felt. It wasn’t just rage – it had a lot to do with love and trying to understand what was happening to us.”

Hassan, however, was less charitable. “The difference between us and hip-hop is we had direction, we had a movement, we had people who kept our eyes on the prize,” he said. “We weren’t just bullshitting and jiving”.

The stubbornly solitary Scott-Heron, meanwhile, always downplayed his alleged influence. In 2010, two years before his death, the New Yorker asked him what he thought when people called him a rap trailblazer. “I just think they made a mistake,” he replied.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.