How the French writers Marguerite Duras and Barbara Molinard first met is unclear, but their friendship was one of such mutual admiration that it now seems a fated union. Different though their lives were, the two women shared an important characteristic: In their fiction, they both offered intimate depictions of the misogyny they suffered. This was unusual, even shocking, for women writers at the time.

By the mid-1960s, Duras was a prolific writer and an acclaimed filmmaker within the French intellectual class. No one knew Molinard. In her 40s, she began to write short fiction and did so with an unusual fervor, sometimes working for weeks without pause. To this day, little is known about Molinard precisely because she did not wish to be known. She went to great pains to ensure this, destroying nearly every page she wrote.

“Everything Barbara Molinard has written has been torn to shreds,” Duras announced in the preface to Panics, Molinard’s collection of grotesque and bleakly antic stories, first published in France in 1969 and released last year in the U.S. in a brilliant translation by Emma Ramadan. Duras was not being hyperbolic; upon completing a story, Molinard would tear each page into pieces, which she piled onto her desk and eventually pitched into a fire. Then she rewrote them: “They were put back together, torn up again, put back together again,” Duras wrote. Only the stories in Panics, which were rescued by Duras and by Molinard’s husband, were spared.

Molinard is far from the only writer to destroy her work. In July 1962, following Ted Hughes’s infidelity and the collapse of their marriage, the American poet Sylvia Plath may have set fire to letters she exchanged with her mother, or her in-progress novel, or some of her husband’s poems. Paul Alexander, in his biography of Plath, Rough Magic, interpreted this as a “bonfire” set in a “fit of rage.” In Sylvia Plath: Method and Madness, Edward Butscher attributes the act to the “bitch goddess” Plath had become. Seven months later, Plath took her own life.

She couldn’t possibly have known that her blunted life would inspire a field of literary scholarship, documentaries and feature films, and subsequent generations of writers and poets. But she certainly understood how little control she had over the way she was perceived, a depressing truth most women learn to accept in their youth. In her book The Silent Woman, a study of biographies of Plath, Janet Malcolm writes, “In any struggle between the public’s inviolable right to be diverted and an individual’s desire to be left alone, the public almost always prevails.” By the summer of 1962, Plath may have felt that the public had already won. Fire would have been consoling, its devastation totalizing.

Perhaps Plath wanted to conceal the personal details she had divulged in her letters or in her novel; we cannot know for sure. What can be sifted from the ashes is that a writer’s reasons for destroying her own work are complex. The act is not the result of a fevered impulse, silly rage—at least, not only these things. Rather, it can be intentional and calculated, a display of ferocious will, an artful final flourish.

In December 1977, the English novelist and poet Rosemary Tonks endured surgery to repair detached retinas in both of her eyes. She was partially blind for a few years after the procedure and went to live in the seaside town of Bournemouth, to convalesce and to escape the disarray of her life in London, where she’d earned a reputation as a champagne-glugging bohemian. Tonks never returned to that way of living; instead, she retreated so thoroughly that the BBC titled its 2009 radio feature about her life The Poet Who Vanished.

It’s somewhat difficult to square the latter part of Tonks’s life with the fizzy and carefree characters who populate her novels. Min, the narrator of Tonks’s novel The Bloater, first published in 1968 and reissued last year, seems the kind of young woman Tonks might have once been. She is chatty, self-absorbed, and delightfully frivolous, always swilling a drink and looking for another pour. Her husband is a terrible bore, so she entertains a handful of intriguing suitors.

For Tonks, the dazzle of that kind of life had dulled by middle age. The decade before her eye surgery was turbulent, beginning with her mother’s sudden death, in 1968. Tonks also had neuritis in her left hand, which made writing exceedingly difficult because her right hand was already damaged by childhood polio. Her marriage fell apart. Searching for solace, she turned to the spiritual realm and eventually found Christianity. She read the New Testament as her sight returned, and traveled to Jerusalem in 1981 to be baptized. Christianity offered her the chance to shed her disappointing past and start anew.

Tonks’s astonishing reinvention could be read as the result of a midlife crisis, or a psychological break, or the ecstatic embrace of religious redemption. But each of these twists her story into something familiar and foregone, rendering the choices she made desperate and piteous. On the contrary, Tonks’s retreat seems to have brought her the peace that eluded her at earlier stages of her life, and allowed her to more fully reject the English society for which she had always felt some mixture of captivation and revulsion. In her 1967 poem “Addiction to an Old Mattress,” she wrote:

Meanwhile … I live on … powerful, disobedient,

Inside their draughty haberdasher’s climate,

With these people … who are going to obsess me,

Potatoes, dentists, people I hardly know, it’s unforgivable

For this is not my life

But theirs, that I am living.

And I wolf, bolt, gulp it down, day after day.

After leaving London, Tonks allegedly checked out her own books from libraries in order to destroy them. She refused requests to reissue her work, which by then included two collections of poetry and six novels. She even incinerated an unpublished manuscript. Tonks allowed herself only one book, the Bible, which she called her “complete manual” for how to live. She was known to stand on street corners handing out copies to passersby.

According to a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, by 1970, women still published only a third of the number of books men published each year in the U.S. Globally, too, Tonks and Molinard and Plath, who began publishing in the middle of the 20th century, were among the first generations of women writers who were not viewed primarily as exceptions to their gender—the way the Brontë sisters, Jane Austen, and Mary Shelley had been regarded. That a woman might be celebrated for her literary efforts, earn recognition and prizes, and enjoy a wide readership were relatively recent developments.

For some women, this new attention brought unexpected scrutiny, as well as the grim realization that their legacy would be dictated by anyone but themselves. As Janet Malcom wrote, “To [her] readers … Plath will always be young and in a rage over Hughes’s unfaithfulness.”

Tonks roundly rejected the idea that a writer whose work is publicly consumed should be obligated to contend with the public. In 1963, more than a decade before her retreat, she told Peter Orr of the British Council, in an interview, “I think it is diabolical, this getting of a poet out of his or her back room and the making of them into public figures who have to give opinions every twenty seconds.”

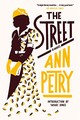

The American author Ann Petry shared Tonks’s stance. Celebrity came to her suddenly following the publication of her first novel, The Street, which follows an ensemble of impoverished characters living in Harlem and ignored by a city disinvested in its Black population. Published in 1946, it was the first novel by a Black woman to sell more than 1 million copies; the resulting sensation thrust Petry into a spotlight she’d never wanted. Misunderstood by white critics, who construed her significant talent as an anomaly and compared her work against that of only a few other Black writers, she wrote in her journal that she felt overexposed, like “a helpless creature impaled on a dissecting table—for public viewing.”

In 1969, Petry agreed to send 19 boxes’ worth of her personal papers to Boston University. She regretted it almost immediately. By the early 1980s, she confessed in her journal that she was distrustful of and baffled by the interest other people took in her private materials: “It never occurred to me that in my lifetime people would be poking through that stuff … Why not? Principally because I tried to disappear.”

In her memoir, At Home Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry, Petry’s daughter, Elisabeth, recalls that her mother spent the last years of her life on a “shred-and-burn campaign.” In the summer of 1983, Petry wrote, “Destroy them, journal by journal, or else edit them. No. Destroy them.” She redacted whole passages of her journals and sometimes replaced them with new writing. In interviews, she offered inconsistent dates for her birth, refused to disclose the date of her marriage, and was known to embellish stories from her childhood. Though these obfuscations could be viewed as self-serving editorialization, Petry did not seem interested in authoring her own mythology, or allowing anyone else to do so. She rejected would-be biographers as well as most requests for interviews.

Petry’s suspicion of what other writers might fashion from her life was warranted. She was constantly misrepresented during her lifetime and forced to accept the flagrant prejudices of critics and the literary establishment. For Petry, the only way to control her story was to prevent it from being written at all.

For eight years, Barbara Molinard wrote devotedly, committing to the page the twisted visions that swarmed inside her mind. The stories in Panics creep and sprawl, like dark tendrils of nightmares that won’t end. They steam with hot-blooded gore, as in a scene where a pharmacist saws off a man’s balloonish hand. Time is ornery: Characters wait years for trains and planes and other people; they travel for weeks but never arrive at their destination. They are plagued by anxieties real and imagined as they battle the opaque logic of social systems and bureaucracies. Molinard’s stories betray a mind keenly aware of the psychological erosion of modern life.

For her part, Molinard seemed somewhat bewildered by her tendency toward destruction. She described a divided self: The part of her that destroyed her work was an “enemy,” and it was this shadowy other who ripped apart and burned her stories.

But surely destruction offered something else, something that publishing her work could not: release from her frustrated toil. The chance to begin anew, at the top of a blank page. The possibility of conjuring from nothing a singular, stark sentence. Because it seems that this routine—destroying, rewriting, destroying again, rewriting again—may have also helped Molinard perfect her work. Perhaps the act of tearing paper was as inextricable to her process as sitting down at the table where she wrote, as the feel of the pen in her hand.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.