It’s a question that seems to arise over and over again: Are dancers athletes?

For Maria Haralambis—a dancer, dance teacher, Pilates instructor, and kinesiologist also known as The Dance Scientist—the answer is an emphatic yes. “Dancers are high-performing athletes,” she says.

According to Haralambis and other experts, dancers have a lot to gain from seeing themselves as athletes—and training more like it. Advances in sports science over the last several decades have revolutionized the way most athletes train. By contrast, dance training has remained relatively unchanged. For many years, the same was true for other “artistic athletes,” like gymnasts and figure skaters. But, recently, they’ve leapt far ahead of dancers when it comes to incorporating science-backed methods into their training programs.

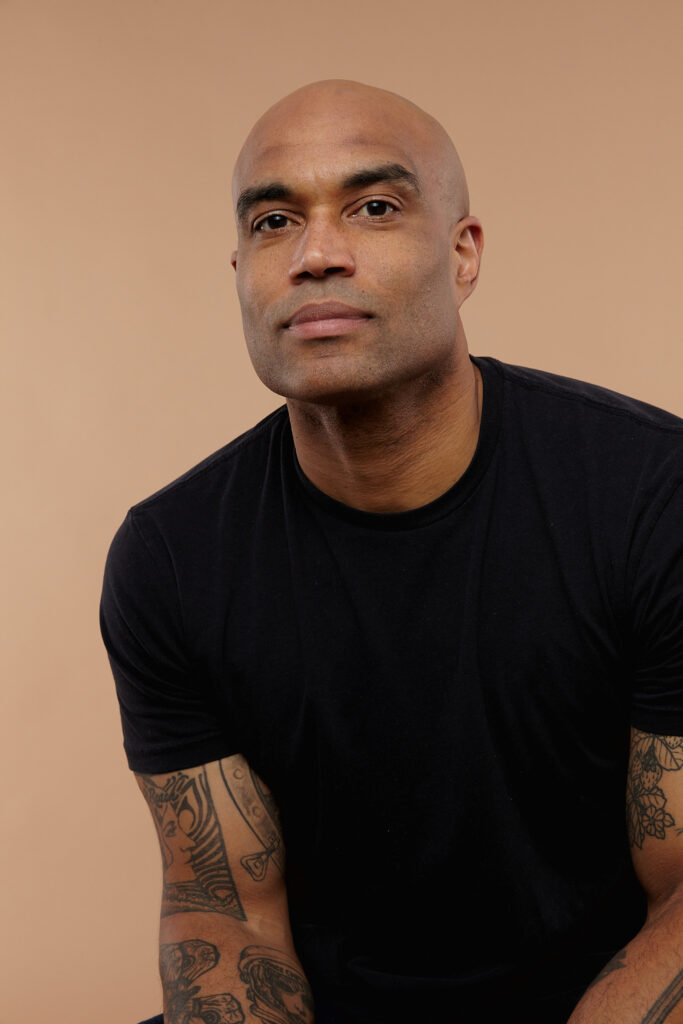

Many in the dance world are resistant to change, and in a way that’s not surprising: When perfection is the standard, and tradition counts for so much, it can feel risky to try anything new. And confusion over whether dancers are athletes also goes both ways. “A lot of people in the sports performance and conditioning world don’t really respect dance,” says Present Tense Fitness co-owner Jason Harrison, a strength and conditioning coach who works with professional dancers from companies including New York City Ballet and the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company.

So, yes, dancers could learn a lot from the field of sports performance. But athletes could stand to learn a few things from dancers, as well.

Dancers Should Be Lifting Weights

It’s time to break the dance-world stigma around strength training. All of the experts interviewed for this article agreed: Adding weight lifting into cross-training routines is one of the most important things dancers can do to increase longevity and reduce risk of injury.

First, let’s bust the biggest myth once and for all: Lifting weights is not going to make you bulk up. “In order to actually increase muscle bulk, you need to train specifically to get larger, and you need to be in a calorie surplus,” says Julia Iafrate, DO, a dance and sports medicine physician at NYU Langone Health who has worked with professional dancers from ballet to hip hop. In other words, to get bigger, you’d have to dedicate a lot of time to weight lifting and eat a lot of protein—so much that it would probably feel difficult. And even the idea that “bulk” is bad is rooted in sexist and racist attitudes that the dance world should work to get rid of, says Harrison.

A common misconception among dancers is that strength exercises need to look exactly like dance movements in order to translate properly to improvements in class or rehearsal. But that’s not the case. “Strength training improves the resilience of your connective tissue throughout your entire body,” says Rena Eleázar, DPT, a physical therapist and sports performance coach who has worked with a wide range of dancers and other athletes, and is a competitive weightlifter and hip-hop dancer herself. Strength training is actually a good opportunity to work muscles that don’t get as much work in dance class, says Iafrate, who notes that it also builds stability, which is especially important for hyperflexible dancers.

That said, there’s always room for some dance-specific movements to help you work toward a particular goal, says Harrison. For example, he recently added some interval-style petit allégro training into his sessions with one client to help her prepare for a season with a new ballet company.

Dancers Should Learn That Less Can Be More

Here’s a statement that might sound sacrilegious but is very likely true: You’re dancing too much.

In dance, “more is better” tends to be the driving ethos. But the truth is that “you do not need to do the exact same jeté over and over again without changing any of your strength or biomechanics,” Iafrate says. “After a certain point, you will not change the dance move.” There’s only so long your body—and brain—can really produce its best effort.

If incorporating better cross-training means replacing or shortening some of your time in class, you might actually find that to be a useful change. Dedicating time to cross-training “is not losing technique time—it’s maximizing what you’re working on in class,” says Haralambis.

You may even need to reduce your overall active time. “Based on the current literature, we know that your risk of injury goes up if you’re doing any athletic activity for more than 16 hours a week,” Iafrate says. “Dance tends to blow that out of the water.”

Dancers Should Taper Before Performance

Sports performance coaches also talk a lot about “periodization,” which refers to a training plan that progresses in a measured way over time, helping to maximize performance and minimize the risk of injury. Athletes’ training plans also generally involve a “taper,” or a reduction in overall workload for a certain period leading up to a big event, allowing time for recovery.

This is pretty much the opposite of how dancers tend to approach training, pushing hardest in rehearsal immediately before, and even the week or day of, a big show. “It’s almost like, if you can survive the process, then congratulations, you get to perform,” says Harrison. Teachers and directors should instead consider having dancers “peak,” or train the hardest, a few weeks before a performance or competition, and then taper.

If all of this sounds like a radical departure from what you know, keep in mind that dance is different these days, too. “We’re asking our dancers to be able to do so much more than they were 20 or 30 years ago,” says Haralambis. “More acrobatic and athletic movements are more and more common in dance.”

Ideally, dancers, teachers, and even directors shouldn’t be on their own to figure all of this out. “A truly modern and progressive approach to dance would have room for strength coaches who think all day about strength, athleticism, resilience, and conditioning for dancers,” says Harrison, pointing to The Royal Ballet as an example of a company that is embracing this model.

What Athletes Can Learn From Dancers

Though dancers may be prone to overdoing it, our attention to detail can also be an advantage. The strong focus on technique in dance training may reduce the risk of some types of injury.

Researchers at the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries, for instance, found that dancers are less likely than other athletes to experience one of the most common sports injuries: tears of the ACL, a knee ligament. That’s despite the fact that dance is full of the kinds of movements most associated with ACL tears, particularly single-legged jump landings. The study also found that, in most cases, there was no difference in the rate of ACL tears between male and female dancers, whereas in other sports, female athletes are significantly more likely to experience this injury. The researchers theorize that dance technique, with its focus on controlled jump landings, reduces the risk of injury and knocks out that gender disparity.

So technique really does matter. And many professional athletes know this, having turned to dance for help improving their agility, coordination, and balance. Numerous professional football players have taken ballet classes to learn to move with more finesse—NFL player Steve McLendon once said that ballet is “harder than anything else I do.” Basketball legend Kobe Bryant even took up tap dancing to strengthen his ankles after a sprain.

Dance has a lot of other sports beat when it comes to our focus on neuromuscular control and technical execution. Where other athletes are ahead of us is in following more carefully designed training plans and prioritizing their recovery. Clearly, we have a lot to learn from each other.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.