A Roege Hove

Manipulating knitted fabric into garments that hug or drape across the body is central to Amalie Røge Hove’s work. The Danish designer studied textiles and knitwear at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, where she “fell in love with the craft”, before working at the studios of Cecilie Bahnsen and Mark Kenly Domino Tan.

Røge Hove launched her eponymous brand in 2019 with a line of stretchy knitted market bags designed as “small sculptures that are shaped by the people who use them”. She followed this with ready-to-wear, debuting at Copenhagen Fashion Week in 2021 and winning the Karl Lagerfeld Award for Innovation at the International Woolmark Prize in Paris this year.

“Knitwear encourages you to be clever in designing shape, texture and details in one,” says Røge Hove. That translates to gauzy high-necked tops, ribbed off-the-shoulder cardigans and sheer dresses that wrap around the body. The other appeal of knitwear, she adds, is there is minimal waste, with all the materials used being part of the finished garment. “My brand is for people curious about material and styling.”

Standing Ground

Michael Stewart has found a way to be rebellious through the conventional. The London-based designer undermines the fashion capital’s reputation for the avant-garde through his collections, which include minimalist strapless gowns and figure-hugging bodysuits. “London is radical in its fashion, but now it seems that being sober is more radical than ever before,” he says. “It’s come full circle to where finish and quality are more unusual because we see so little of them.”

Stewart, who is originally from County Clare, launched Standing Ground in 2022 and presented his first show as part of Fashion East last year. Unlike many of his contemporaries, the designer works to a made-to-measure model, which he says is more sustainable, and allows him to focus on craftsmanship. “Cutting for an individual’s body is important,” says Stewart. “Especially if it is for something special like an evening dress, which I mostly produce.”

His aim is for Standing Ground to sit at the intersection between past and present. “The look could be from a sci-fi movie, or akin to something depicted in a carving or on a stone wall,” adds Stewart, who designed a statuesque gown for Imaan Hammam for this year’s Met Gala. “I take inspiration from the standing stones in Ireland and different ancient relics.”

Setchu

There aren’t many designers who are as au fait with a roped shoulder as they are the intricacies of a puffer jacket. But Satoshi Kuwata, who was awarded this year’s LVMH Prize, has a uniquely varied skill set: he got his start at Beams, trained as a fitter at Huntsman, collaborated with Kanye West and did a stint at The North Face.

Kuwata’s own brand Setchu, which he launched in Milan in 2020, straddles the cities and cultural influences that have informed his career. “People wouldn’t necessarily think my collections come from Savile Row, but it’s about trying to use that knowledge and find a balance between tailoring, fashion and sport,” he says.

Spanning menswear and womenswear, Setchu’s collections include double-breasted blazers, jackets with kimono-style ties and tailored shirts. Japanese minimalism and timelessness are the parameters he works to. “I’ve found that people who consume luxury goods want classic garments that fit nicely.” To reflect this, 70 per cent of Kuwata’s collections are carry-over styles.

Another key feature is adaptability, with dresses that dismantle or sweaters that unbutton into different styles. “I travel all over the world for fishing, and some of the destinations you can’t take lots of clothes… so I decided garments should be able to turn into two or three different shapes,” says Kuwata.

Diotima

“I always had this sense of responsibility to present something from the Caribbean that involves people from the Caribbean,” says Rachel Scott of the motivation behind starting her brand. “Quite often we are referenced, but people in the Caribbean are never engaged with, and I always had a problem with that.”

Scott, who previously worked at Costume National in Milan and Rachel Comey in New York, launched her brand Diotima in 2021, simultaneously referencing and subverting the tropes of her home Jamaica through design. “I don’t want to do something that’s nostalgic or that feeds into clichés of what Caribbean style is. I’m trying to offer a new perspective while having this material grounding in craft.”

Scott steers away from the combination of red, yellow and green, while always using luxury materials in her work. In her hand, the marina or string vest, which every Caribbean has “millions of”, is transformed into a figure-hugging two-piece, hand-embellished with crystals, or a voluminous dress that resembles broderie anglaise. “Caribbean style is less about the actual pieces and more about a certain attitude or nonchalance,” adds Scott. “There’s often a tension within fashion, like mixing a marina with a suit, which is quite interesting and sexy.”

Di Petsa

Dimitra Petsa started thinking about the “eco-feminist” relationship between women and water while studying design at Central Saint Martins. She started a series of Wetness performances with her friends, “where we would drape and clothe our bodies in wet fabric”, as a comment on how women are taught to be ashamed of their bodily fluids.

The Greek-born designer translated this feeling into her brand, launched in 2019, which centres around garments that accentuate the body’s natural form. One of her recurring styles is the Milking corset, which has popper openings at the cups and which “can also be worn symbolically, even if you are not breastfeeding, as an act of self-love”. Or the Undressing jeans, which are designed to be worn with the waistband open, to allow for an expanding belly. “Our body changes all the time and I think it’s important that our lived experience is reflected in our clothing.”

Petsa’s signature, however, is the Wetlook dress – worn by model Gigi Hadid and musicians Ciara and SZA, among others – which is made bespoke from a recycled mesh produced from post-consumer recycled water bottles. Adds Petsa: “The Wetlook dress is a symbol of self-acceptance and honouring of your fluid state.”

Commission

Jin Kay and Dylan Cao’s brand takes influence from their Asian heritages – including the working wardrobes of their mothers from the ’90s – fused with what they see in New York’s Garment District, where their studio is. “We are often inspired by people around the city,” says Kay, who previously worked at Prabal Gurung. “The area near our office is quite the melting pot of tailored suits with workwear and activewear touches.”

As such, their womenswear designs for Commission – which launched in 2018 – include oversized khaki trench coats, suits that layer at the knees and pencil skirts styled with technical jackets. They added menswear in 2021, which “has grown to be a big part of our business”, adds Cao, who was an accessories designer at R13 before launching this brand. “A lot of our girlfriends love wearing tailored pieces and trousers as well – this mix and variety is a big part of our brand DNA.”

As well as offering a less ornate approach to officewear, the duo want to counteract the stereotypical motifs of Asian culture that are often depicted in the west. “We want to highlight Asian-American voices in the industry,” says Kay.

Ester Manas

Most of Ester Manas and Balthazar Delepierre’s designs are one-size, owing to techniques the duo have developed that allow their garments to fit all body types. “We had to think about the right fabrics and right construction in order to adapt to any shape,” says Manas. “Tulle and stretchy fabrics are our go-to, but we try to propose different fabrics while still maintaining the inclusive sizing. It’s a technical challenge, but it’s what our brand is about.”

The Brussels-based designers, who are partners in business and life, launched their brand in 2019 and made their Paris Fashion Week debut in 2021. Their collections are made mostly with recycled and deadstock fabrics and have a decidedly grunge-meets-Y2K aesthetic: wispy chiffon or lace is ruched into halterneck tops or skirts, while gowns and trousers have cut-outs and cascading ruffles.

Their designs have been embraced by some of the key figures of the body inclusivity movement – from musician Lizzo to model Alva Claire and actress Barbie Ferreira.

“If we can help change the industry, from casting to size offerings, it’s all for the better,” adds Manas. “But we mostly want body inclusivity to become so natural that it won’t even be a topic any more.”

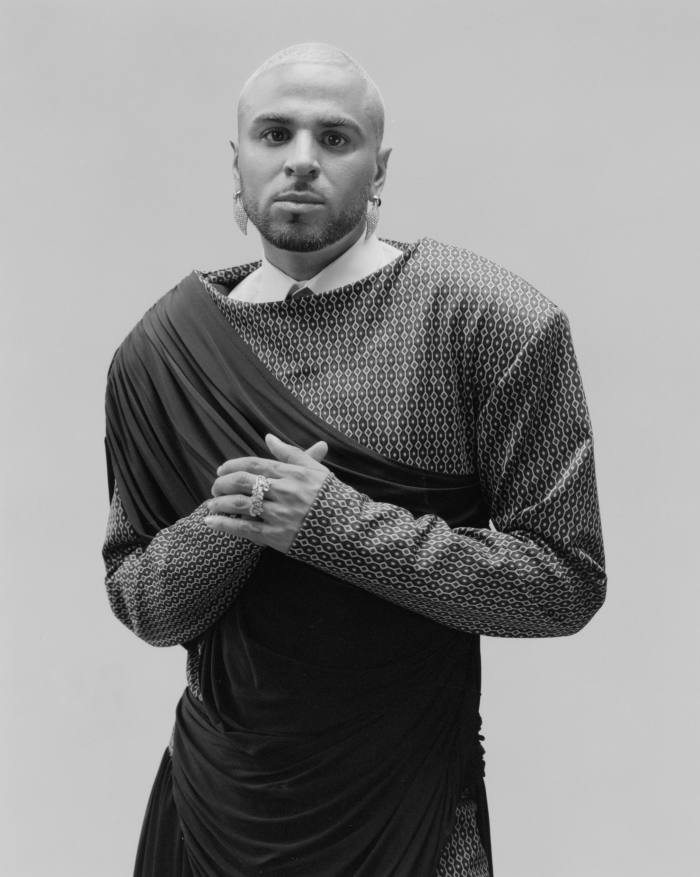

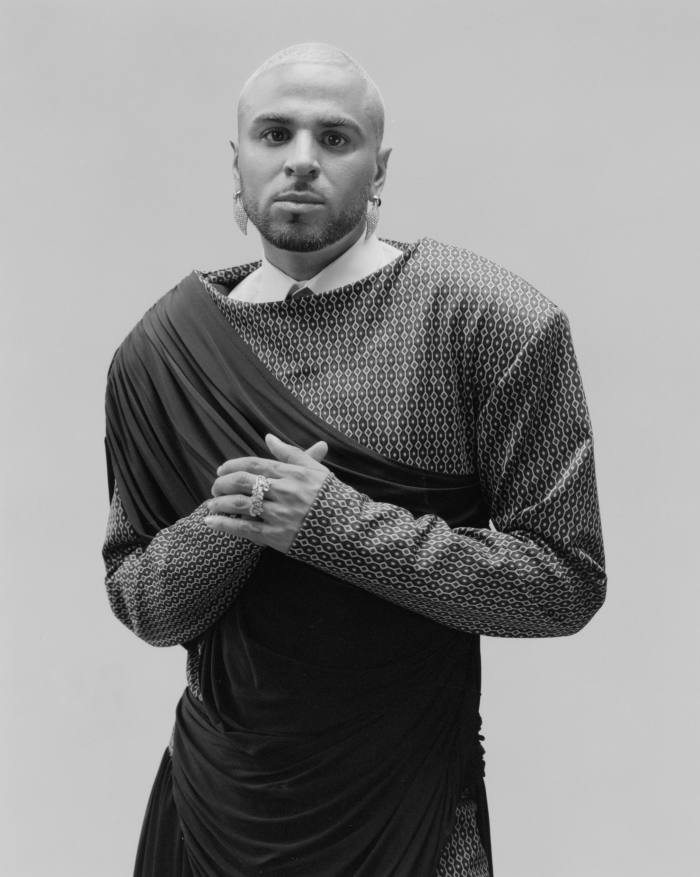

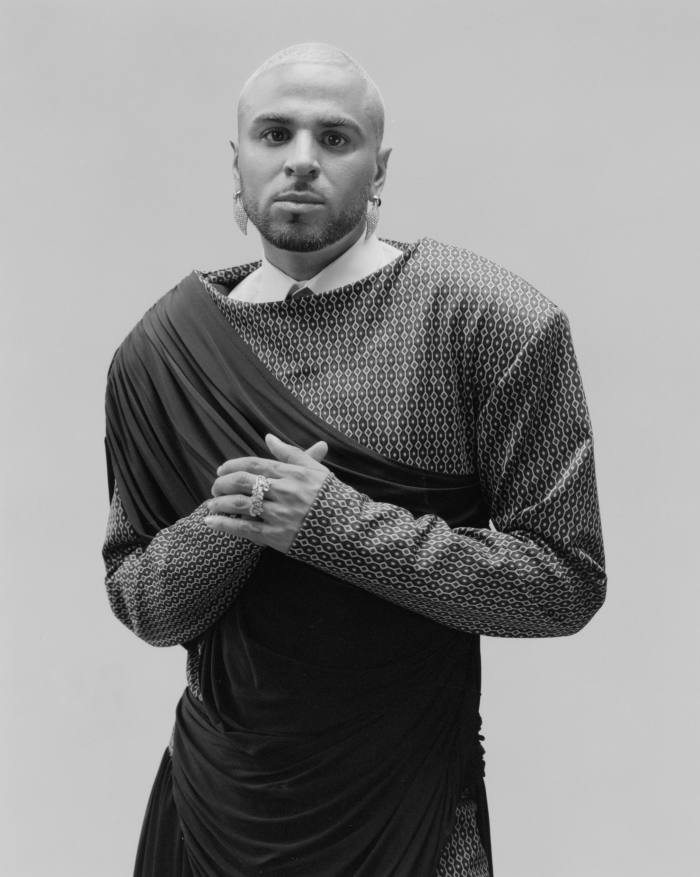

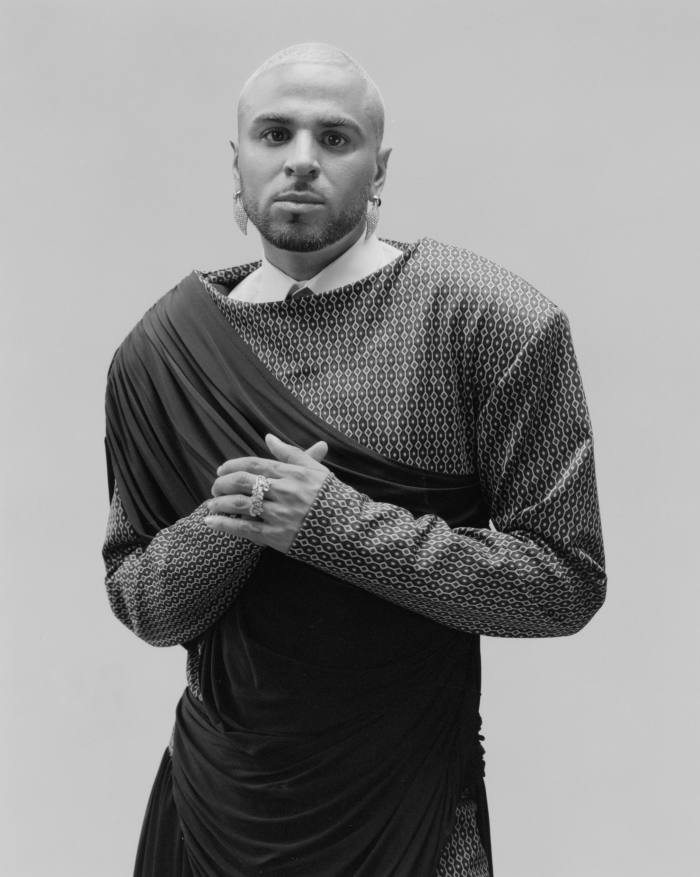

Luar

Raul Lopez knows how to create buzz. His Ana bag – a small, boxy design with sculptural top-handles – sold out within hours when it launched in 2021, and earned him the CFDA’s Accessories Designer of the Year award last year. Meanwhile his shows at New York Fashion Week, the most recent of which closed the proceedings, draw on the pageantry of ballroom culture and don’t have enough seats to meet demand.

The Brooklyn-based designer’s career, however, hasn’t been linear. Lopez launched Hood By Air with Shayne Oliver in 2006, before leaving to start his own brand – Luar Zepol, his name spelt backwards – in 2011. While he had some success, Lopez struggled to keep the business afloat, putting the label on hold in 2014, and then after relaunching, pausing it again in 2019.

His current iteration, Luar, appears to be on a less treacherous trajectory; he’s stocked at Dover Street Market and Moda Operandi, was nominated for the LVMH Prize this year, and his accessories, which still command waiting lists, are providing that all-important financial stability.

Lopez’s ready-to-wear often takes the banal – a white office shirt with a tie or chinos – and gives it a high-fashion spin. He draws on his Latin and working-class roots as inspiration, creating a space “where social class goes out the window”. Adds Lopez: “Luar is like the YMCA of fashion – it’s a place where all walks of lives can join and hang out and feel confident enough to feel comfortable in their own skin.”