In the Land of the Free, anyone can have a dream… unless, of course, you aren’t a white man of middle-class status, in which case you can have a dream by all means – they’re free to anyone, much like abject poverty – but you’re going to have to have God on your side if you attempt to bring it to fruition. However, for those seeking just a small taste of that dream, then for a reasonable fee, there is always the American Song Poem Anthology, or at least there was during the pomp of counterculture.

It is much to Uncle Sam’s credit, however, that this gaping chasm of opportunity hasn’t stopped people from eyeing the main chance from afar and often taking the leap. The cultural boom of home recording lived and died on this very tenet of Americanism. As the famed architect Maya Lin once said, “To me, the American Dream is being able to follow your own personal calling. To be able to do what you want to do is incredible freedom.” In the American Song Poem Anthology, we get to hear what that sounds like. It is, in many ways, the album that defines the US more than any other.

So, how is it so definitive? Well, it comes down to ‘cultural hegemony’. This is a phrase used to describe the way in which America exports iconography around the world as a subtle means of control. In short, it refers to the impoverished locals sitting around in some war-ravaged village in a subjugated country, suddenly saying to their friends, ‘America can’t be too bad. I mean, have you ever had a Coca-Cola and listened to Elvis? I think it’s pretty clear that we’re the baddies here’. The complicating factor when it comes to American cultural hegemony, however, is that it seems to prove most effective on home soil.

This image of freedom, this notion that anything is possible and everyone gets a fair shot, is upheld by the likes of the aforementioned Mr Presley, who snake-hipped his way from a lowly life into the history books. Hell, Marilyn Monroe started out in an orphanage, got a job painting army supplies in a war-effort warehouse and ended up a trailblazer who even made her mark in the White House; if that is not proof of dreamy social mobility, then what is? The reason these two primed examples have been selected is that they emerged a matter of years apart amid the great explosion of pop culture.

The rise of youthful arts finally did away with the idea that music and anything else that induced fame belonged to the virtuosos—the days of pompadour prodigies who could play a symphony backwards for kicks were over. Enter the folks who had something to say, and if they said it in the right way, then surely everyone would hear it. This in itself was also a first. By the dawn of the 1960s, just about everything was new, from the Planned Parenthood Act of Connecticut in 1965, bringing the pill into people’s lives to Pet Sounds pioneering stereo sound, sex on TV, and lava lamps.

Suddenly, the stilted lives of the 1950s were shaken up as though humans had invented fire for the second time. You could finish work, rush into town, hear a new genre of music pumping from a newfangled machine called a ‘jukebox’, pick up a partner, head home and listen to the brand-new Van Morrison record in crisp hi-fidelity sound, get it on without any fear of parenthood putting a stop to all the fun in the months following and wake up to a breaking announcement on colour TV about a president losing half of his brain near a book depository. This was bound to blow the minds of an entire generation; how could it not?

The notion of dreams was also intensified by the simultaneous hardship. Seeing The Beatles become gods at the same time your brother is being shipped off to war would certainly send a signal of some sort about fame and fortune. Enter the rise of private pressings whereby people took the matter of becoming the next Beatles into their own hands. The public had their own vinyl made out of hard-earned savings.

This was revolutionary and very prescient for the modern age with AI-assisted creation. For better are for worse, there are gatekeepers in the art world, as there are in every walk of life. The difference is that art is subjective. If you want to be a surgeon, you have to pass a test; if you want to be the next Usain Bolt, only your times will tell. However, if you want to be a musician, you don’t even have to be able to play an instrument; just ask anyone who knew Sid Vicious. Private pressing circumnavigated the gatekeepers of the art world and got straight to business.

When this new notion of substance over skill combined with the inherent glossy-eyed aspirations of Americans and increasing disposable income, the maddening world of private pressing burst open almost as an inevitability. Then, the American Song Poem Anthology made the whole thing even easier; all you needed was a pen. For all the negativities that undermine this madness, it is people like Bobbi Blake, who pressed a record about liking yellow things, which oddly included notably orange tangerines, that makes the USA a truly wonderful place.

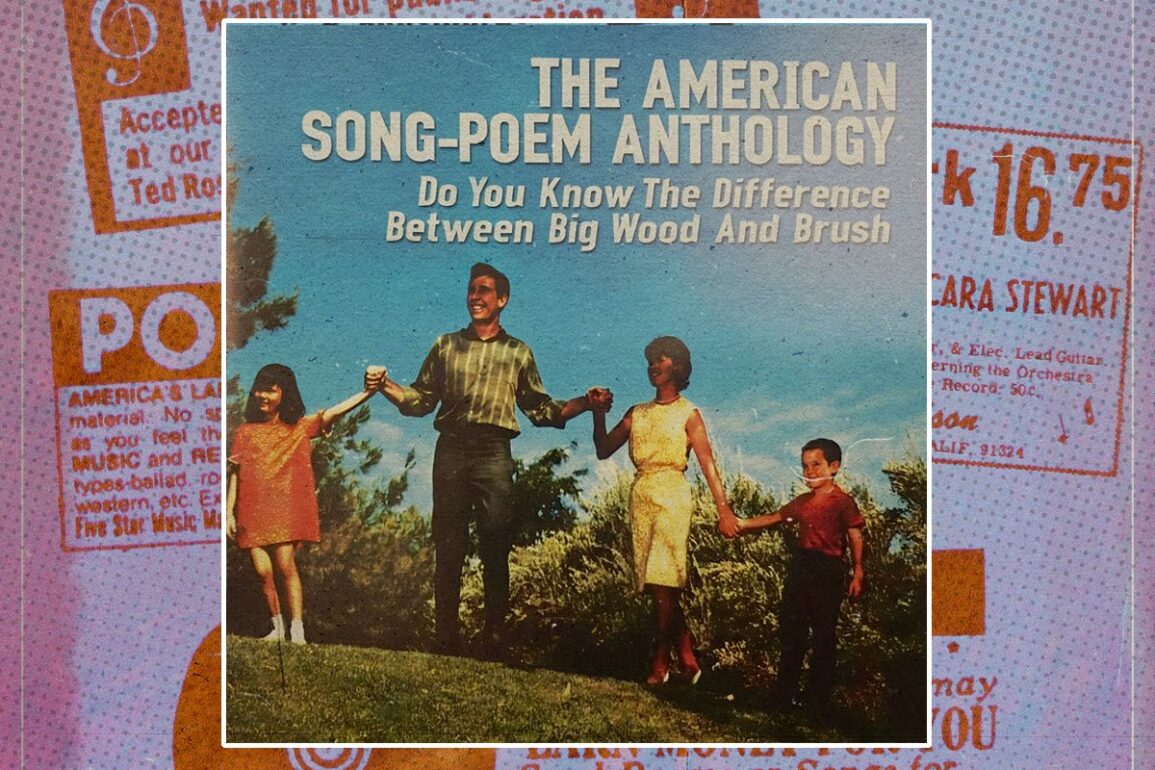

This musical microcosm flourished following the birth of pop culture when everyone was after a piece of this newfound thing called fame or, at the very least, wanting a quick 15-minute feel of it. The American Song Poem Anthology was a capitalist enterprise that involved the good people of the US sending off poems and a few hundred dollars to be turned into songs by established but disenfranchised session musicians of the day.

Naturally, the poems were far from submissions from some Joni Mitchell / Toni Morrison hybrid and, instead, pertained to subject matters such as the empowering affirmatives of the president in ‘Jimmy Carter Says Yes!’ to the tale of a blind man’s penis in the song predictably and then suddenly unpredictably titled ‘Blind Man’s Penis (Peace and Love)’ which contrary to what you might think, has a heart of gold somewhere amid the unhinged lyrical dirge. Or take the wildness of ‘Gretchen’s New Dish’, which may or may not be about a six-year-old cooking a new recipe.

The issue was that this scheme and many similar enterprises that popped up resulted in widespread chronic depression among the skilled musicians who once wanted to hold esteemed residencies in jazz clubs with their name on the door but instead wound up trying to turn ‘The Duck Egg Walk’, a track about a man who eats a duck egg every day and ends up moving in with a farmer and his family after seemingly turning into a duck, into a pop hit. This literally led to suicides among musicians. They had previously been earning a good wage in front of paying audiences, but the rise of recorded music meant that they were being replaced in clubs by jukeboxes and forced to seek income, swindling the salt of America for poems that they would quickly transpose onto to a regurgitated tune and charge $50-$100.

You can check out the mad results of this very American enterprise below.